Having thoughts about suicide is one of the possible criteria for a depressive disorder. However, it also occurs in other mental health problems, including addictions, personality disorders, and psychotic disorders. 1 in 25 people have ever thought about suicide. Below you can read more about suicidal thoughts to help you understand and to cope with them.

What are they?

People experience suicidal thoughts in various ways. It can be a vague desire or a very concrete idea or plan. You may be thinking about the consequences of suicide, or you imagine what your funeral would be like. You can fantasize about the different ways to end your life or you search for information on the internet. You can also experience the thoughts as intrusive, frightening, or coming from outside of yourself, or as an internal desire or relief.

There is a distinction made between the type of wish in suicidal thoughts:

- Passive ideation. Life has been difficult for you lately, and you find it challenging to deal with. A common thought is, for example, “Life is exhausting” or “It would be peaceful if I were gone.”

- Active ideation. You have the desire to stop living and have taken steps to act on it. For example, you thought about the form of suicide, you made a concrete plan, you wrote a farewell letter, or arranged practical matters after your death.

Cause

While suicidal thoughts may seem like a desire to die, they are often a reflection of the desire to escape a difficult situation and not wanting to live anymore. Often, it is an expression of despair or hopelessness. If you experience significant problems for a longer period and become depressed as a result, it can become increasingly difficult to see or find a way out. When you feel trapped, it can happen that the idea of death becomes appealing. Some people find it frightening, others find it reassuring to have a kind of ‘solution’ at hand.

What can you do?

- Suicide can feel like a sensitive subject, but talking about it can make it feel less heavy and can help you deal with it. If you find it too scary to talk to your surroundings, discuss it with your doctor, therapist, or a professional from 113 suicide prevention via 113.nl or call 0800-0113.

- It’s important to understand that having suicidal thoughts does not necessarily mean that you want to die. It can help to think that they are there because you have not yet found a solution to your problems.

- If you become anxious, it’s important to realize that having a thought does not mean you will immediately act on it. It’s good to be aware, but you don’t have to be afraid that you will lose complete control.

- Create a safety plan to prevent deterioration or to help you in case of a crisis.

- If there is a possible crisis, it is important to contact the right caregivers. You can contact 113 for help or contact a crisis service through your doctor. If there is an acute emergency or life-threatening situation, call 112.

Sources:

https://ggzvoorelkaar.nl/hulp-onderwerpen/suicidale-gedachten/

What are core beliefs?

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) is a widely-used form of psychotherapy that focuses on the connection between thoughts, feelings, and behaviours. One of the key concepts in CBT is the idea of core beliefs. Core beliefs are deeply held beliefs that individuals have about themselves, others, and the world around them. These beliefs can be both positive or negative, conscious or unconscious and often reflect broad generalised judgements.

Core beliefs are formed on the basis of our experiences and interactions with others. They are often developed early in life or during stressful and traumatic periods. Factors such as our upbringing, family dynamics, culture, societal norms, experiences at school can also influence core beliefs.

How do they impact me?

Core beliefs act as the lens through which we see the world and can have a significant impact on the way you interpret experiences, process information and interact with others and the world around you. Thus, people with different core beliefs might experience and interpret the same situation in different ways, and think, feel and behave differently. Unhelpful or negative core beliefs, even if inaccurate, can therefore lead to negative automatic thoughts. Negative automatic thoughts are habitual and pop into our minds in response to certain situations or triggers.

See below for an example of how two different people can interpret the same situation differently based on their core belief.

Situation: Two people receive a bad grade on the same test

| Core belief | Automatic thought | Feeling | Behaviour | |

| Person A | I am incapable | I never do anything correctly.. What’s the point? | Depressed | Drops out of the course |

| Person B | I am mostly capable if I have put work into it. | I did badly because I did not revise enough for this test. | Disappointed | Signs up for the re-sit with revision plan. |

Uncovering your core beliefs

The first step in addressing negative core beliefs is to identify them and become aware of them. This can be done through therapy sessions, self-reflection, and journaling. By recognizing and naming these beliefs, you can begin to understand how they are impacting your own thoughts, actions and mental health. You can try to look for patterns, or themes in your own thinking and emotions. For example, think about the situations you typically find difficult and thoughts that come up in these situations. Are there certain labels you use to describe yourself or others? There are three main types of negative core beliefs about the self:

- Helplessness

- Unlovability

- Worthlessness

Below you can find some common negative core beliefs people have:

- I am unlovable

- I am worthless

- I am a failure

- I am not good enough

- I am ugly

- I am stupid

- I am weak

- I am a loser

- The world is dangerous

- The would is unpredictable

- People are not to be trusted

Changing your core beliefs

Once negative core beliefs have been identified, you can begin to challenge these beliefs and replace them with more accurate, realistic ones. By identifying and challenging negative core beliefs, you can break the cycle of negative thinking and develop more realistic, adaptive beliefs, leading to improved mental health and a more fulfilling life. Your therapist can help you to do this in treatment or you can use the thought record in the app to help you challenge some of your beliefs.

Resources:

https://www.therapistaid.com/therapy-worksheet/core-beliefs

Beck, J. S. (2020). Cognitive behavior therapy: Basics and beyond. Guilford Publications.

Disappointment is the feeling you get when something you hoped for doesn’t happen. Regret is the feeling you get when you think you could have prevented something undesirable by acting differently. The difference between these two emotions is that with disappointment, you have no influence, for example, when your football team loses, while with regret, you could have done things differently. These feelings make you reflect on whether your expectations were realistic in the first place, thus preventing future disappointment, regret, or mistakes.

What-if thinking

You process disappointment and regret through what-if thinking (also known as counterfactual thinking). This means thinking about alternative situations and outcomes. There are two types of what-if thinking:

- Upward counterfactual thinking is focused on improving a situation. For example, “If I had left 5 minutes earlier, I wouldn’t have missed the bus.” This helps you learn from your mistakes.

- Downward counterfactual thinking is focused on how the situation could have been worse. For example, “I came in third, but at least I wasn’t last!” This helps you feel better about the situation.

Too much or too little

What-if thinking is very healthy when you feel disappointed or regretful. However, there are some situations where it can become problematic:

- If you are perfectionistic or have a strong focus on self-improvement, you may become tense due to the large amount of upward counterfactual thinking. You regret more quickly because you always see room for improvement and feel obligated to do better next time. This can also lead to anger towards yourself if you fail to prevent mistakes.

- If you tend to procrastinate, for example, because you feel down, you may unconsciously apply too much downward counterfactual thinking. You convince yourself that it can always be worse, which causes you to have little motivation to change. This can contribute to maintaining your negative feelings.

Avoidance of disappointment or regret

If you find disappointment or regret difficult emotions to experience, you may have a strong tendency to avoid them at all costs:

- If you have often experienced disappointment or find it difficult to tolerate this emotion, you may always keep your expectations as low as possible to avoid disappointment. This form of pessimism leaves little room for positive emotions.

- Conversely, you can also leave your expectations unchanged and hold on to unrealistic hope. For example, by convincing yourself that your partner won’t cheat for the fourth time after three times. Hope is then a kind of deferred disappointment, and you avoid actively doing something with your emotions and the situation.

- You may have the illusion that control drastically reduces the chance of regret and mistakes. Think of reading all the reviews when buying a new product. Although it is good to reduce risk, if you are afraid of regret, it can also hinder you if you never dare to take risks. For example, you may be afraid to change jobs.

- Thanks to empathy, you are able to understand what others feel. However, this can also lead to feeling responsible for preventing disappointment in others and thus meeting their expectations. This may cause you to go beyond your own limits.

Take home message

If you recognize yourself in the examples above, it’s important to realize that disappointment and regret are normal emotions to experience. It’s healthy to have these feelings and they are functional and useful for your development. Making mistakes, taking risks, and daring to learn from your choices contribute to developing your self-confidence and sharpening your insight and decision-making skills. In the short term, it may feel uncomfortable at times, but in the long term, it will benefit you more!

Sources:

Keith D. Markman, Igor Gavanski, Steven J. Sherma &, Matthew N. McMullen (1993),

The Mental Simulation of Better and Worse Possible Worlds, Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, Volume 29, Issue 1, p87-109,

Markman, K. D., & Miller, A. K. (2006). Depression, control, and counterfactual thinking: Functional for whom? Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 25(2), 210–227.

Sirois, F.M., Monforton, J. and Simpson, M. (2010) “If Only I Had Done Better”:

Perfectionism and the Functionality of Counterfactual Thinking. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin , 36 (12). 1675 – 1692.

Sirois, F.M. (2004) Procrastination and counterfactual thinking: avoiding what might have been. British Journal of Social Psychology, 43 (2). 269 – 286

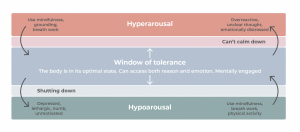

The Window of Tolerance explains why some people react more intensely to stress than others. The model is used with trauma, but it can also be used in other situations in which you experience stress. Together with your therapist you will increase your Window of Tolerance: make your window bigger. By doing this you can learn to recognize your own signals in time and learn to effectively handle stressful situations well.

What is the Window of Tolerance?

The concept of Window of Tolerance was introduced by Siegel in 1999. Siegel’s theory gives a good explanation about how emotions can fluctuate. Stress is part of life. A little stress now and again is not necessarily a bad thing and often a good thing; stress can make you more resilient. It is still possible to function well with stress. It is normal to sometimes feel a little more tired, less alert or more irritated and at other moments a little better about yourself. These feelings are within a healthy tension range. You are able to interact well with the people around you, you are able to think, you can empathize with others, you are open to new experiences, you can learn and you can control yourself when necessary. If you experience a particularly stressful situation, you are able to handle it well.

The zone in which someone can handle stress well is called the Window of Tolerance in psychology. If you experience stress and know how to deal with it effectively, you are in your Window of Tolerance. When stress or tension becomes too great or lasts too long, there are two directions you can go in. Are you above your Window of Tolerance? Then you are too tense. We call this hyper arousal. You then go into a ‘fight or flight’ mode: you are irritated, tense and you cannot relax properly. There can be a few different reasons why this happens: something stressful has happened, you worry excessively or, for example, you have slept poorly. In any case, you are not able to put things into perspective and cannot interact effectively with other people. Are you under your window? Then you are not tense enough. We call this hypo arousal. You feel depressed, understimulated, numb and unmotivated You feel stuck in this feeling.

What happens to your body when you are stressed?

Stress releases stress hormones that quickly prepare the body to fight, flee or freeze. The instinctive part of the body takes over. Your body will recover once the stressful situation is over: your heart rate and breathing return to normal, your blood pressure stabilizes, your muscle tension decreases and your digestive system starts working again. For example, when you are comforted or take time to relax, it allows your stress system to calm down. As long as the stress stays within your Window of Tolerance, someone can function properly. But if the stress lasts for a long time and surges past this window, it can become problematic. This is unhealthy and causes long-term stress. It can eventually lead to exhaustion or sickness.

The stress system can become so sensitive that it reacts intensely in situations that are not dangerous. Your brain interprets a situation as threatening or dangerous and the stress system is immediately activated. You then find it very difficult to cope with the stress effectively, meaning that your Window of Tolerance has become much smaller.

Trauma and Window of Tolerance

It is possible that your Window of Tolerance has become much smaller due to a traumatic event and that you quickly feel out of balance. Together with your practitioner you will look for ways to increase your Window of Tolerance.

Increasing your Window of Tolerance

Do you feel like you are always above or below your Window of Tolerance? You are not alone. It often happens that people feel too stressed and/or too numb. You can learn how to better cope with these feelings, and develop skills under the guidance of your therapist. Below are a few examples:

- developing emotion regulation skills

- Learning grounding skills and connecting with the here and now. This technique can be used if you are experiencing flashback or dissociation.

- deep and slow breathing exercises to help you feel more relaxed.

- communicating with others: Learning to tell others how you feel.

- have fun and laugh, for example dancing and singing. This also improves our fitness and breathing

Sources

https://www.psychologievandaag.nl/zelf-doen/de-kunst-van-het-wachten-en-de-window-of-tolerance/

https://nielsvansanten.nl/stress-in-je-lichaam/stress-je-hersenen-en-het-window-of-tolerance/

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U8gLstY6dYc

https://henk50.wordpress.com/2019/07/20/emoties-5-window-of-tolerance/

https://embodiedfacilitator.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/Centring-Mark-Walsh-ebook-v2.pdf

https://www.victimsa.org/blog/trauma-and-window-of-tolerance

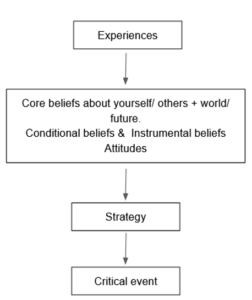

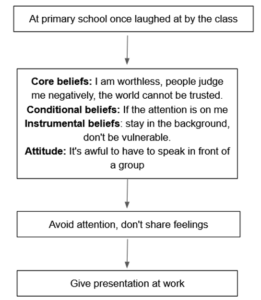

Beck's Cognitive Model is a model that assumes that psychological complaints arise from the way in which information is selected, interpreted and processed. This process starts early in childhood and is influenced by many factors.

The model describes the following elements:

- Experiences: Relevant learning moments from the past.

- Beliefs:

- Core beliefs are beliefs about how you view yourself or others and your perspective on the world or future.

- Conditional beliefs are beliefs with an "if..., then…" nature. If A happens, that's the condition for event B.

- Instrumental beliefs can be seen as ‘rules of life’. It is an important value to someone.

- Attitudes: The least profound reaction, such as assessing a particular situation to be undesirable.

- Strategies: A response to the beliefs, the techniques a person develops to survive in life. These can also reinforce our beliefs.

- Critical event(s): A situation that is perceived as problematic.

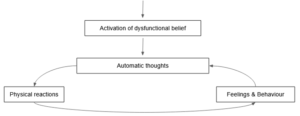

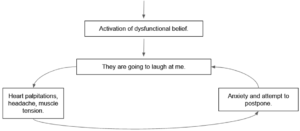

- Activation of dysfunctional beliefs: During a critical event, a certain cognitive schema or belief is triggered. If it is dysfunctional, it triggers a negative vicious cycle of automatic thoughts, feelings and behaviour and physical reactions.

Beck’s Cognitive Model

Example of a completed model

Sources:

Ten Broeke, van der Heiden, Meijer & Hamelink, Cognitieve Therapie de basisvaardigheden, 2008.

Beck, A.T. (1987). Cognitive models of depression. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy: An International Quarterly, 1, 5-37.

Learning to manage your anger involves adopting new ways of reacting that are more in line with your values or goals and result in more positive outcomes for yourself. Before reading this article, we suggest reading the article on understanding anger and Anger management exercises part 1 to prepare yourself.

In this article, you will find some tips and several exercises that you can perform to help you manage your anger effectively in the moment.

Remove yourself from the situation

One of the best ways to manage your anger in the moment can be to simply remove yourself from the situation or circumstances that are causing you to feel angry. If you are not sure how, or if you can manage your anger in the moment, take some time on your own and leave.

Anger is an emotion, a temporary state that flares up and reduces over time. By removing ourselves from the situation, we give ourselves time to calm down and think about how we would like to respond to the situation.

If anyone else is involved in these situations, you can prepare them by explaining what you are going to do in advance and practise things to say to politely excuse yourself from these situations.

Distract yourself

Distraction can be an effective short-term technique to reduce anger in situations which you cannot resolve or change.

As mentioned in the article about understanding anger, there is a back-and-forth relationship between our thoughts and our anger. Distracting yourself will therefore prevent you from retriggering yourself and increasing your anger. It can also serve as a good way to get rid of some of that built-up energy.

Try doing an activity which requires your attention. Think about a demanding physical activity, or an activity which requires effort and focus, for example playing sports, cleaning your house, finishing your work, or doing some painting. You can also try evoking strong physical sensations, for example by taking a cold shower, tasting something very sour or spicy, listening to some music, something that makes you dance or gives you a good feeling.

Write down each distraction skill and rate your anger before and after performing the exercise to determine which is the best skill for you. For example:

| Distraction skill | Anger Before 0-10 | Anger After 0-10 |

| Take a cold shower | 7 | 3 |

Find out what works for you and write yourself a small action plan.

Reducing physical sensations

Another skill to reduce the experience of anger is reducing the physical response associated with anger. For example: when we are angry, our body temperature increases. This is where phrases such as ‘blood boiling’ come from. Lowering your body temperature can therefore send a signal to your brain that your anger is becoming less intense and, therefore, it is an effective strategy for reducing anger. Try going outside, taking a cold shower, or holding an ice pack against your head.

Other techniques include engaging in intense physical exercise to release some of the energy and arousal, or to practise a relaxation exercise to induce physical relaxation. Check out our library on relaxation and practise the technique that suits you best.

Express your anger

Anger is an important emotion that often arises when you feel something is wrong, when you sense a threat or if you feel that you are being mistreated. Therefore, being able to express it effectively and being heard is vital and can help you to regulate your anger.

Unfortunately, most people do not enjoy being the target of anger and, therefore, they naturally avoid the situation or fight back. Therefore, your chances of being heard and getting your needs met are reduced. Thus, it is a very useful skill to be able to express your anger effectively. A good exercise is to develop a script to express your anger. Use the points below to develop your own script, and write it down somewhere you can access it whenever you need it.

- Describe the situation that made you angry. Try to be as clear and objective as possible. Avoid writing from your own perspective, opinion or judgements.

- Explain your feelings. Try to use I-statements such as ‘I feel’ and ‘I think’.

- State your needs and wants. Try to be as specific and clear as possible. For example, what do you need from them? What can the other person do to help you get rid of the issues you just mentioned?

- State how fulfilling your needs or wants will benefit them. For example, it will improve your relationship, or make you more willing to help them as well.

- Write down the compromises you are willing to make.

These are just some of the steps you can take to help you manage your anger more effectively. Each step and each exercise will take practise and patience until you can put them to use in an effective way. Don’t forget to focus on the improvements you have already made and reward yourself for the steps you have taken.

Do you want to learn more about these skills and other exercises you can try out? You can find them in The Dialectical Behavior Therapy Skills Workbook for Anger.

Reference:

Chapman, A. L., & Gratz, K. L. (2015). The dialectical behavior therapy skills workbook for anger: Using DBT mindfulness and emotion regulation skills to manage anger. New Harbinger Publications.

Learning to manage your anger involves adopting new ways to react that are more in line with your values or goals and that result in more positive outcomes for yourself. As a first step, it is important you have a good understanding of what anger is exactly and why it arises. Therefore, before reading this article, we suggest you read this article on understanding anger first.

In this article, you will find some tips and several exercises that you can perform step by step to help you prepare for managing your anger effectively.

Motivation

Motivation makes an important contribution to effective behavioural change. By increasing your motivation, you have a bigger chance of success and will show more perseverance when things get difficult. Therefore, a valuable exercise can be to become aware of the effect that anger has on your life. How is it impacting you, both positively and negatively? How does it impact those around you and/or your relationships? Is anger preventing you from reaching important goals or values?

You can use the table below and fill out the sections that apply to you:

| Value | How you would like things to be | How does anger interfere with your values? |

| Relationships with friends | ||

| Relationships with family | ||

| Relationship with partner | ||

| Work | ||

| Spiritual/religion | ||

| Recreation | ||

| Health & fitness | ||

| Other: |

Identify your anger cues

Reflect on the moments during which you get angry: are there particular situations, sensations or experiences which cause you to feel angry? Does it occur when you feel attacked or criticized, for example? Or maybe it’s when you feel people are acting in a wrong way?

Other common examples include:

- When someone disagrees with you

- When you experience physical or emotional pain

- When you are being told ‘no’

- When you’re not able to express yourself or your opinion

Keep track of the moments you feel angry with the help of the app. Write down what happened, how you felt, what you were thinking and what happened afterwards. After a while, look back at what you wrote down, do you notice any patterns?

What regularly caused you to feel angry? Are there any overarching themes?

Taking care of yourself

Anger – and emotions in general – is difficult to manage and can feel overwhelming at times. Therefore, trying to manage anger takes significant effort and helpful resources. Furthermore, it has been suggested that emotional regulation is a finite resource, thus, when you are low on resources/energy, your emotions become more difficult to manage. Think about the last time you couldn’t sleep or when you skipped a meal. Were you a bit more irritable or sensitive than you normally are?

You can replenish your resources by taking care of yourself; our physical state is interconnected with our mind. Getting enough sleep, eating healthy, and staying fit, for example, can help to replenish your resources. When you are not in a good physical state, you have less resources at your disposal and, therefore, will be more vulnerable to your anger. A big part of managing your anger consists of ensuring that you have the available resources at your disposal.

Read our lifestyle library and write down any improvements you can make.

Avoiding your anger cues

Your resources also become depleted as you use them. You can compare this to exercising your muscles. When you lift a heavy object, your ability to lift it reduces over time and while your muscles are still tired and achy, you probably won’t have the strength you had at the start. The same thing happens with your anger: if you are regularly provoked and have already spent a lot of resources on regulating your emotions, you will have less resources left to manage them the next time you are provoked. Therefore, avoiding your anger ‘cues’ if possible is also an effective strategy to help you manage your anger more effectively.

Take a look at the list of anger cues you made earlier: are there any situations, things, or people you can try to avoid? Make a plan of what steps you can take to help you avoid or limit your anger triggers.

For example: if getting stuck in traffic causes you to feel angry, plan to take a less busy route to work.

These are just some tips and exercises you can use to put you in a stronger position to deal with your anger when it arises. In part 2, you will find some more tips and exercises you can use to manage your anger or rage in the moment itself.

Do you want to learn more about these skills and other exercises you can try out? You can find them in The Dialectical Behavior Therapy Skills Workbook for Anger.

Reference:

Chapman, A. L., & Gratz, K. L. (2015). The dialectical behavior therapy skills workbook for anger: Using DBT mindfulness and emotion regulation skills to manage anger. New Harbinger Publications.

If you’re reading this article, it is likely that you struggle with anger. In that case, it is important to know that you are not alone. In fact, 45% of employees report losing their temper at the office regularly and a study by Romanov (1994) found that 15% of people scored very high on hostility.

Anger is one of the basic human emotions: we all experience it to varying degrees from time to time. However, intense and poorly managed anger can cause distress and problems in your daily life. Poorly regulated anger can have a negative impact on, for example, our relationships, our mental health and our work. Think about shouting at your colleague or acting aggressively toward a friend. In fact, poorly regulated anger can worsen situations and often ends up increasing your own anger.

Learning about anger and how to express it appropriately and gaining insight into your own anger can have a positive impact on your practical and social life. The goal of this article is to help you understand anger as a first step to help you acquire skills to manage it in a better way.

Anger as an emotion

Anger is an emotion that lies on a spectrum ranging from annoyance to frustration, intense rage and hate. Intense anger can be a very powerful and overwhelming experience. It charges you and prepares you to take action. It is part of your natural defence system; your ‘fight or flight’ response. Anger does not necessarily make you ‘fight’, but it is an emotion that helps you to stand up against injustice, stand up for yourself and others if you feel attacked, and make changes where necessary.

You experience anger when you detect that something is wrong, when you sense a threat or if you feel that you are being mistreated. It tells other people to listen to you. Therefore, anger is often also warranted and is, therefore, a very important emotion! Think about important social movements for equality and the motivation to right wrongs.

Common things that cause you to feel anger:

- Situations you perceive as threatening, such as when someone insults you or a loved one, it can be considered as a threat to your well-being or status.

- Being prevented from reaching an important goal, such as being stuck in traffic, causing you to be late for work.

- Unpleasant physical or emotional sensation such as pain, such as when accidentally cutting yourself with a kitchen knife.

As with any other emotion, anger is a brain and bodily response or reaction to events or thoughts we are experiencing. Therefore, it is temporary and will flare up and die down if you allow it to run its course.

Tip: This is important to keep in mind if you are learning to manage your anger!

Continue to the next article on experiencing anger to help you become aware of when you are experiencing anger, which is an important first step in learning to manage your anger.

References:

Chapman, A. L., & Gratz, K. L. (2015). The dialectical behavior therapy skills workbook for anger: Using DBT mindfulness and emotion regulation skills to manage anger. New Harbinger Publications.

https://www.mindyouranger.com/anger/anger-statistics/

Anger is one of the basic human emotions. Emotions are generally made up of 4 components: thoughts (cognitive), physical reactions, tendency/actions (behaviour) and facial expressions. By being able to identify some of these components in your own experience of anger, you are more likely to be aware of when you are feeling angry, which is a solid first step to being able to manage it more effectively!

Physical reaction

As mentioned, anger is an energizing emotion, which is matched by our physical response. Be on the look-out for physical cues such as:

- Increased heart rate

- Increased sweating

- Tense muscles

- Clenched jaw/fists

- Dry mouth

Cognitive (thoughts)

This component has to do with what you are thinking when you are experiencing the emotion. Common thoughts when you’re feeling angry are:

- I hate this person/thing

- This is unfair

- This situation is wrong

- This person is annoying or inconsiderate

- They shouldn’t be doing that

One common thinking pattern when you’re feeling angry is rumination. Rumination is when you think of the same things over and over again. Think of when you are stuck in traffic, and you keep thinking about how late you are going to be and why the car in front of you is moving so slowly. Rumination actually causes you to feel angrier. There is a back-and-forth relationship between our thoughts when we are angry and the feeling of anger we experience.

Behaviour

Anger is often accompanied by the urge to make a change or take action. Some common examples of behaviour or actions we take when we are feeling angry are:

- Aggression (not always)

- Shouting / talking quickly

- Expressing our anger

- Seeking revenge

- Harming someone else

- Proving someone else wrong.

- Setting things straight

References:

Chapman, A. L., & Gratz, K. L. (2015). The dialectical behavior therapy skills workbook for anger: Using DBT mindfulness and emotion regulation skills to manage anger. New Harbinger Publications.

Many studies in positive psychology have shown that gratitude is associated with happiness. It is important that you regularly reflect on what you are grateful for. Many addicts struggle with feeling that they are not good enough or feel that they have failed as a result of their years of addiction.

A person is naturally inclined to focus on the negative aspects. Therefore, it is understandable that when you are at the beginning of your recovery process, you are mainly focused on what could be improved or what you find difficult in your life. Motivate yourself to start keeping a gratitude diary. It will help you to be more optimistic in and content with life. You will also be more friendly with regard to your social environment, such as your friends and family, because you won’t be focusing solely on yourself.

What are you grateful for?

On a daily basis, either at the end or start of your day, reflect on three things that you are grateful for. This can be something very small, such as ‘a compliment from a colleague’. Or something big, such as gratitude for your good health.

The more concrete you define your points, the more you will experience the feeling of gratitude. Furthermore, try to think of new things each time. If you lapse into the same points every day, there is a chance that you will start to consider it as something ‘normal’.

Questions to help you experience more gratitude

- What happened today that you are grateful for? Example: I had a nice day at work.

- Who helped you today? Example: a good friend who checked a cover letter for you.

- Who surprised you in a positive way today? Example: a cheerful bus driver who happily wished you good morning.

- Have you laughed at something or someone today? Example: a smart comment from your child.

- Were you touched by something you have seen, heard or read today? Example: a nice article in the newspaper.

How often?

Try to write down three points daily, at a fixed time. If this is not feasible, do it every week on a fixed day. If you regularly reflect on what you are grateful for, you will notice the greatest effects.