Below, you can find a list of activities and situations which people with panic attacks are known to avoid. You should indicate to what extent you avoid these activities and/or situations that make you feel unpleasant or anxious. Indicate the degree of avoidance for when you are with someone you trust and for when you are alone.

Scoring:

1 = I never avoid it

2 = I rarely avoid it

3 = I avoid it sometimes

4 = I usually avoid it

5 = I always avoid it

For example, Jan always avoids lifts, but never when he is with his wife:

Lifts → together (1) – alone (5)

Below, you can find the list of situations and activities. You can skip the situations that do not apply to you.

Places

Theatres together __ alone ___

Supermarkets together __ alone ___

Shopping centre together __ alone ___

Classrooms together __ alone ___

Department stores together __ alone ___

Restaurant together __ alone ___

Museums together __ alone ___

Hitchhiking together __ alone ___

Theatre or stadiums together __ alone ___

Garages together __ alone ___

High places together __ alone ___

Enclosed spaces / tunnels together __ alone ___

Open spaces:

Outdoors (e.g. fields, wide roads, squares) together __ alone ___

Indoors (e.g. spacious rooms, large foyers) together __ alone ___

Transport:

Bus together __ alone ___

Train or tram together __ alone ___

Underground / metro together __ alone ___

Airplane together __ alone ___

Boat together __ alone ___

Driving a car:

On smaller roads together __ alone ___

On the highway together __ alone ___

Riding as a passenger in a car:

On smaller roads together __

On the highway together __

Other situations:

Queuing together __ alone ___

Crossing a bridge together __ alone ___

Attending parties together __ alone ___

Walking on the street together __ alone ___

Being home alone together __ alone ___

Being far from home together __ alone ___

Other:

…. together __ alone ___

…. together __ alone ___

…. together __ alone ___

…. together __ alone ___

Source: Keijsers, G. P. J., Van Minnen, A., Verbraak, M., Hoogduin, C. A. L. & Emmelkamp, P., (2017). Protocollaire behandelingen voor volwassenen met psychische klachten.

A generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), also known as worrying disorder, is characterized by long-lasting, excessive and non-reality-based anxiety. You can constantly feel threatened, uncomfortable and restless, and you may always feel like something’s going wrong. The consequence is endless worrying over all kinds of daily issues and finding the worrying very difficult to control.

Your daily functioning and ability to maintain social contacts can suffer greatly due to an anxiety disorder. The feelings of anxiety and concern are usually accompanied by restlessness, difficulty concentrating, irritability, fatigue, increased muscle tension and/or trouble sleeping.

Origins of an anxiety disorder

Generalized anxiety disorder usually develops around the age of 20. The cause of the disorder is not known exactly but has to do with a combination of factors, such as heredity, neurobiological characteristics, long-term stress, major events, personality and upbringing.

Metacognitive therapy for generalized anxiety

The treatment used with GAD is called metacognitive therapy. The model associated with the treatment of GAD is based on the distinction between the content of the worrying (negative thoughts about events) and the negative interpretation of the worrying (worrying about worrying). An example of this is “Oh help, I am going crazy with all this worrying” or “see, all this worrying is giving me heart complaints”. Worrying about worrying increases the anxiety and negative thoughts, therefore creating several vicious circles.

Metacognitive therapy focuses on exploring and changing the positive and negative views you might have about worrying. This treatment focuses on the beliefs someone has about their own thoughts rather than on the content of the thought themselves. The treatment consists of fourteen sessions, which are divided into four phases. Homework exercises, such as registering complaints daily and conducting behavioural experiments, are agreed upon during each session. An example of such a behavioural experiment is the ‘worry delay’ experiment.

Source: Keijsers, G. P. J., Van Minnen, A., Verbraak, M., Hoogduin, C. A. L. & Emmelkamp, P., (2017). Protocollaire behandelingen voor volwassenen met psychische klachten.

With an exercise that is called a Thought Record, you can organise your thoughts, feelings and behaviour, helping you discover patterns and dysfunctional behaviour. If you can understand why you think and feel in a certain way and what the consequences of this are, you can start making changes. It is important to clearly distinguish between the event, thoughts, feelings, behaviour and their effects.

You can answer the following questions:

- Event: What happened? Describe from an objective perspective.

- Feeling: Briefly describe how you feel. Feelings can often be physical (anxious, angry, sad, happy).

- Thoughts: What were your thoughts? What went through your head, what did you say to yourself?

- Behaviour: What did I do? What didn’t I do? What did others do or didn’t do?

- Result: What was the result? Describe the consequences of your behaviour.

Below, we give you an example of a completed Thought Record:

| Event | Describe the moment in which you had the unpleasant feeling. (Tip: keep it short!)

I was walking alone when I saw someone I knew on her bike. I waved at her, but she just cycled past me. |

| Feelings | How do you feel and how strong was this feeling?

Scared, sad. |

| Thoughts | Describe the immediate thought (s) that preceded this feeling (s)

She’s angry at me. She doesn’t like me anymore. I am worthless. |

| Behaviour | What did you do? How did you react?

I looked down and quickly walked home. |

| Consequences | What consequence did this have?

I cried and didn’t dare to speak to her again, because my insecurities were confirmed.

|

Tip: A tip for learning to distinguish between thoughts and feelings is to recognise that thoughts take place in your head, while feelings tend to be bodily sensations. For example: “During a robbery, I thought I would not survive, and I felt very anxious about this. Therefore, the thought was: I don’t think I’m going to survive. The feeling was: I feel anxious.”

Thought record exercise

Think of a recent incident during which you experienced fear. Make sure this situation is specific, for example: “Yesterday, when I went out for breakfast, I got very anxious because of a man who was acting suspiciously.”

The thought record exercise is available in the NiceDay app.

Sources:

Keijsers, G. P. J., Van Minnen, A., Verbraak, M., Hoogduin, C. A. L. & Emmelkamp, P., (2017). Protocollaire behandelingen voor volwassenen met psychische klachten.

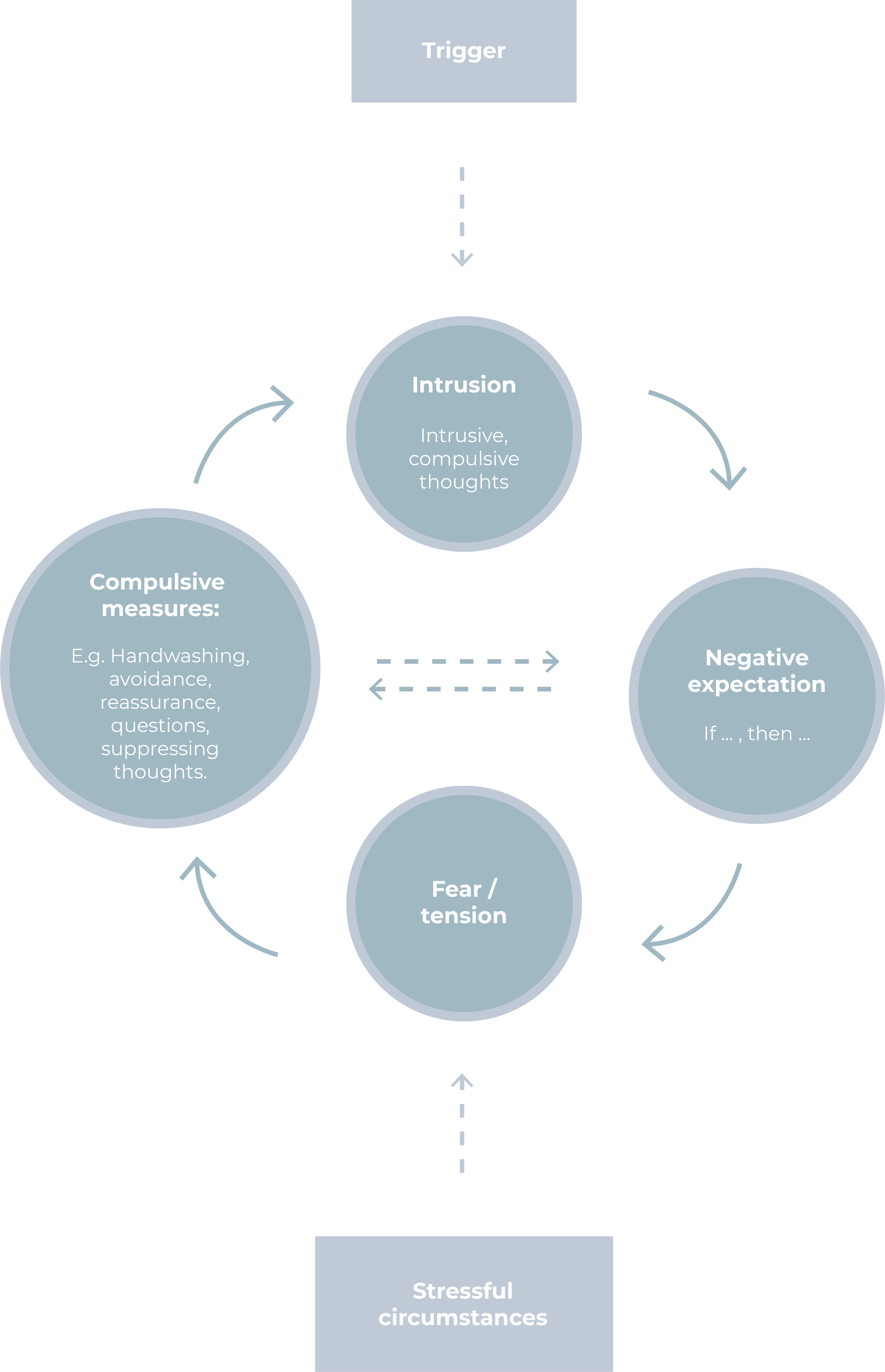

What happens if you suffer from an obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD)? Below, you can find a schematic representation.

Also take a look at the page about Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder or Obsessive Disorder.

We call an intense fear of a certain animal or insect an animal phobia (zoophobia).

The most common animal phobia in the Netherlands is a phobia for spiders. About 10% of the population is afraid of spiders.

When you are suffering from an animal phobia and are confronted with your fear, you may experience accelerated breathing, a dry mouth, excessive sweating, nausea and headaches. In some cases, you may even experience tremors, confusion, stomach cramps, chest pain, and extreme panic reactions, such as screaming and flight behaviour.

How do you know if you are suffering from an animal phobia?

When someone suffers from an animal phobia, they can experience:

- A persistent excessive or unreasonable fear when the animal/insect is nearby.

- An anxiety reaction when in the presence of the animal/insect, which almost always arises immediately and can lead to a panic attack.

- Recognition that the fear of the feared animal/insect is excessive or disproportionate.

- Avoidance of the animal/insect or tolerating this animal with intense fear or stress.

- Problems in daily functioning that are caused by the anxiety reactions or concerns about having the phobia.

- Persistent anxiety that lasts for at least six months.

Causes

The emergence of an animal phobia can have various causes. A traumatic event (such as being bitten by a dog) can lead to the development of a phobia. Phobias are also known to run in families to some extent. In addition, some people are more prone to develop a phobia.

Upbringing also plays a role. Parental behaviour is often adopted in childhood, which means that you, like your parents, will react fearfully to spiders, for example.

In many cases, there is no clear cause for the development of the phobia. However, that does not mean that you can never get rid of it.

Therapy

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy has been shown to be the most effective in treating an animal phobia. An important part of this is exposure; being confronted with the animal or insect which evokes the fear. This can be in your imagination or in reality. Every step of the treatment is taken in consultation with your practitioner.

Sources:

https://www.psycom.net/anxiety-specific-phobias/

https://kindtclinics.com/genezen/?f=Arachnofobie

https://www.thuisarts.nl/angststoornis/hoe-ontstaat-angststoornis

https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/anxiety/exposure-therapy-anxiety-disorders

https://www.verywellmind.com/prevalence-of-phobias-2671911

Have you noticed that you have certain types of thoughts that keep recurring? Or that you regularly think in a certain way, thus becoming habitual? The different ways of thinking are called ‘thinking styles’. Thinking styles have such an automatic character that you are often not even aware of them. Thinking styles can be positive but can also have a negative side. When a negative thinking style is recurring, it can affect you negatively. These negative thinking styles do not always correspond with reality, which is why we sometimes call them ‘thinking errors’.

There are many different types of negative thinking styles. Some are more common than others, but you can find the most well-known in the table below. By becoming aware of your thinking styles, you can also begin to correct yourself. Which ones do you recognize in yourself?

| Thinking style | Characterized by | Example of thoughts |

| Mental Filter | You mainly focus on the negative. You do not take neutral or positive events into account or tend to experience them as negative. | – I did some shopping for my mom, but I forgot one thing. I am so stupid!

– I passed my test, but I couldn’t even answer the easiest question. How stupid am I?! |

| Catastrophizing | You exaggerate the consequences. You experience situations as disastrous, terrible or intolerable. | – If I don’t hear from her soon, then I’m sure she died in an accident.

– The presentation will go wrong and then they will fire me immediately. |

| All-or-nothing thinking | You judge situations in extremes. Something, for example, either happens never’ or ‘always’. Something is either entirely good or entirely bad. With you, there is no middle ground. | – If I’m not a perfect parent, then I’m a completely worthless person.

– If I don’t sleep for 8 hours, I’m completely off all day. – If I can’t do this, then I can’t do anything. |

| Personalizing | When you take something personally, you think that everything people do or say has something to do with you. You put all the responsibility and guilt on yourself or your actions. | – He must be cranky because I didn’t run the errands.

– When people look at me at a party, I think “there is something wrong with me”. – She was catty to me because I did something wrong. |

| Mind-reading | You think you know what someone else is thinking. You fill in for others what they think of you. | – She looks at me and thinks I’m boring.

– If I ask her to take me into account, I’m sure she’ll get angry. – She thinks I don’t know anything about this. |

| Must-thinking | When you use this thinking style, you have rules and norms that you and others must meet. If you or others don’t meet these rules, you feel horrified. | – I should always be ready to help another. If I don’t help them, I’m a bad friend.

– It is terrible that I made a mistake. I should always do it right. |

| Emotional reasoning | You use your feelings as proof that your thoughts are correct. | – I feel like I’m not capable, so I’m not going to succeed.

– I feel scared, so this is dangerous! |

| Overgeneralization | You draw a general conclusion based on one or a few experiences. | – I passed the test. I might as well quit school now!

– I’m always unlucky! |

| Predicting the future | You think you know what will happen in advance. | – I ordered a package, but I know for sure that it will arrive when I’m not there.

– If I leave home earlier, there will definitely be a traffic jam.

|

| Measuring with two different scales | You are more critical of yourself than you are of others. | – If others show their emotions, that’s okay. If I do it, it is a sign of weakness.

– Others may make mistakes, but I have to do everything right.

|

| Exaggeration or downplaying | You make something bigger than it is or you wrongly write something off. | – I got a good grade for a test, but it was very easy, so it doesn’t count. |

| Excluding the positive | Positive experiences do not count or are suppressed. | – I received a compliment that I look good, but it’s not that big of a deal. |

| If only I had | You often worry about situations from the past, without it being of any use to you. | – If only I hadn’t made such a crazy comment.

– If only I had left home earlier, I would have been on time. – If only I had done things differently, my relationship would not be over now.

|

| Drawing hasty conclusions | You take on a negative perspective when there is no evidence to actually support your conclusion. | – Someone responds to my nice comment without a smile. Apparently, he doesn’t like me.

– Someone is ignoring my message on WhatsApp. Apparently, I am not worth responding to.

|

| Labelling | You have a negative opinion about yourself, without considering whether this is actually a reflection of reality. | – I didn’t know the answer to his question. I am such a loser.

-I was a few minutes late for work today. I am such a bad employee. |

| Bringing up the past | You selectively remember situations from the past. | I am having bad luck again. Today I was late, 2 weeks ago I forgot an important meeting and last month I was sick for an entire day! |

| Box thinking | This is an extreme form of overgeneralization. Instead of describing a mistake, you immediately pigeon-hole people. | – I drove through a red light. I am such a bad driver.

– He forgot a friend’s birthday. He is such a typical bad friend. |

When you suffer from blood-injection-injury phobia, you experience an intense fear or strong aversion when you are confronted with situations that involve blood tests, hypodermic needles, vaccinations, operations and diseases. Someone with this phobia tends to avoid hospitals, doctors and dentists. The disadvantage of avoiding situations like this is that it can have major consequences for your health. After all, never going to the dentist is not good for your teeth.

Symptoms

When someone who’s dealing with this phobia is faced with a situation that he or she fears, they may experience symptoms such as:

- accelerated breathing

- a dry mouth

- excessive sweating

- nausea / dizziness

- headache

- trembling

- confusion

- stomach cramps

- chest pain

- panic reactions; screaming / flight behaviour

- feeling faint / passing out

What distinguishes the blood-injection-injury phobia from other phobias is that some people dealing with this phobia have a tendency to pass out when faced with an anxiety-inducing situation. Research has shown that about 50% of people with a needle phobia and 75% of people with a blood phobia suffer from fainting.

Causes

The development of a blood-injection-injury phobia can have various causes. It can result from a negative experience, for example during a blood test. Furthermore, experiencing a panic attack during a specific situation or witnessing a traumatic event (a bloody accident, for example) can also be a cause.

Therapy

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy is effective for treating blood-injection-injury phobia. This tyepe of treatment focuses on discussing and treating the behaviour and thoughts that sustain the fear. An important part of this is exposure therapy, during which you will actively expose yourself to the anxious and frightening situations.

Your practitioner can guide you to overcome this fear by gradually exposing you to the anxious situations.

Sources:

https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/anxiety/exposure-therapy-anxiety-disorders

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4079768/

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) is a type of psychotherapy. Would you like to learn more about CBT or prepare for your treatment? In this 3 minute video, you’ll learn everything you need to know about CBT. You can also read the explanation below the video.

The CBT treatment focuses on discussing and treating the behaviour and thoughts that sustain your problems. You will investigate the connection between your thoughts, feelings and behaviour, and you will learn how to turn the thoughts that generate unwanted feelings into helpful thoughts that create desired feelings instead. The effectiveness of CBT has been proven in scientific research. Treatment is complaint- or problem-oriented and generally takes a short amount of time. The goal is to learn to think more realistically and become more balanced. Even after treatment, you may still experience situations as difficult, but you will no longer see them as a ‘disaster’.

Part of CBT involves filling out thought records, challenging thoughts, and doing both exposure assignments and behavioural experiments.

Consistency of thoughts, behaviour and feeling

Thoughts, ideas and perception play an important role in psychological complaints. For example, people with major depressive disorder often find that minor disappointments or setbacks can elicit a pattern of negative thoughts about themselves, about the future, and about the world. These negative thoughts almost become automatic.

The way you think determines your perspective on situations. Two people who find themselves in the same situation may react very differently. As an example, we take Jan and Piet, who board the same bus. On this bus, a group of children suddenly bursts out laughing. Jan thinks: “I’m sure they are laughing at me”, giving him a sad feeling. He gets off at the next bus stop because he feels too uncomfortable. Piet thinks: “Oh, those kids are having a good time, they must have had a nice day,” and this gives him a pleasant feeling. Piet stays on the bus until he reaches his destination and gets off cheerfully. This is an example of how the same event can evoke a different feeling in two different people; because of their automatic thoughts, they interpreted the situation differently. Thoughts influence how you feel, and, luckily, our thoughts can be changed!

Cognitive therapy

Cognitive therapy is a systematic method that helps you to understand these thoughts that lead to unpleasant feelings. By learning to think differently, you can reduce your negative feelings.

There are three steps in the cognitive part of the therapy:

- At first, you learn to become aware of the negative automatic thoughts (e.g., “They laugh at me because they don’t like me”).

- Then, you learn to challenge these negative automatic thoughts and beliefs by asking critical questions about them (e.g., “Is there evidence for this thought, could I look at the situation differently?”).

- Finally, you will consider whether other interpretations are possible and learn to create a new, more realistic thought (e.g., “The children are not laughing at me, but at each other”).

The behavioural part of the therapy

Your thoughts can influence your feelings and behaviour. Conversely, your own behaviour can also reinforce your negative automatic thoughts. Think back to Jan who got off the bus. Because of his behaviour, he did not learn that his thoughts may have been wrong. In fact, the other kids might not like him because he left so suddenly. That is why you will not only examine your thoughts, but you will also work on your behaviour. You do this by doing exercises, such as experiments or exposure exercises. Together with your professional, you will learn to put your new behaviour into practice.

In the end

The CBT treatment aims to teach you how to think more realistically and to be able to deal with your complaints. Remember that you can still experience situations as difficult even after finishing your treatment, but the treatment will help you to no longer see them as a ‘disaster’. You conclude the treatment by making a relapse prevention plan, which gives you the confidence to be able to deal with difficult moments in the future.

Bron: Keijsers, G. P. J., Van Minnen, A., Verbraak, M., Hoogduin, C. A. L. & Emmelkamp, P., (2017). Protocollaire behandelingen voor volwassenen met psychische klachten.

If you are being treated for a compulsive disorder, your treatment will often involve exposure treatment. To ensure successful exposure, it is best to take these basic principles into account:

- Test your compulsive thoughts: Do your fears actually come true? Keep testing this.

- Test your If-then expectation:

– Always state what exactly you are afraid of (disaster) in advance

– Did this actually happen?

– Is this surprising?

– What did you learn? - Merge them together: Try to perform several exposure exercises simultaneously. For example, if you suffer from social anxiety, you could tell a joke at a party, wear a striking sweater, and chat with a stranger. Usually, you tend to try them one by one, the next step is to combine them.

- Confront yourself: If you want change, you have to do something about it. Consciously seek out frightening situations that cause the anxiety to (re)surface. Experience the anxiety completely.

- Variation: Try to vary between the exposure exercises as much as possible. Practice during as many different situations as possible. It also helps to conduct exposure exercises in your imagination. For example, you could write a movie script about your most feared situation.

- Experience feelings: Experience your emotions during the exposure exercises and do not try to change them.

- Discard the compulsive behaviour: Keep in mind that the compulsive behaviour is not just having a negative impact on your daily life, but that this behaviour also sustains the compulsion, as well as providing false security.

- Attention: Stay focused on the exposure exercise and avoid distractions.

- Tension: The aim of the treatment is to test the expectations, not to avoid tension. Don’t be afraid of tension.

- Reminder: Remember the successful exposure exercises. Find a tangible object that will remind you.

When you suffer from an illness anxiety disorder – also called hypochondria – you are scared of catching a serious illness or are convinced that you are currently suffering from or will suffer from a serious illness. If this fear is very strong and lasts longer than six months, we call it an illness anxiety disorder.

Symptoms

People with illness anxiety disorder are characterized by:

- compulsively checking their body for signs of illness

- avoiding or compulsively looking up information about diseases

- seeking reassurance from others

- continuous over-concern about having an illness

- physical reactions to the fear, such as a headache, palpitations or dizziness

- frequent visits to the doctor

Factors that sustain the anxiety

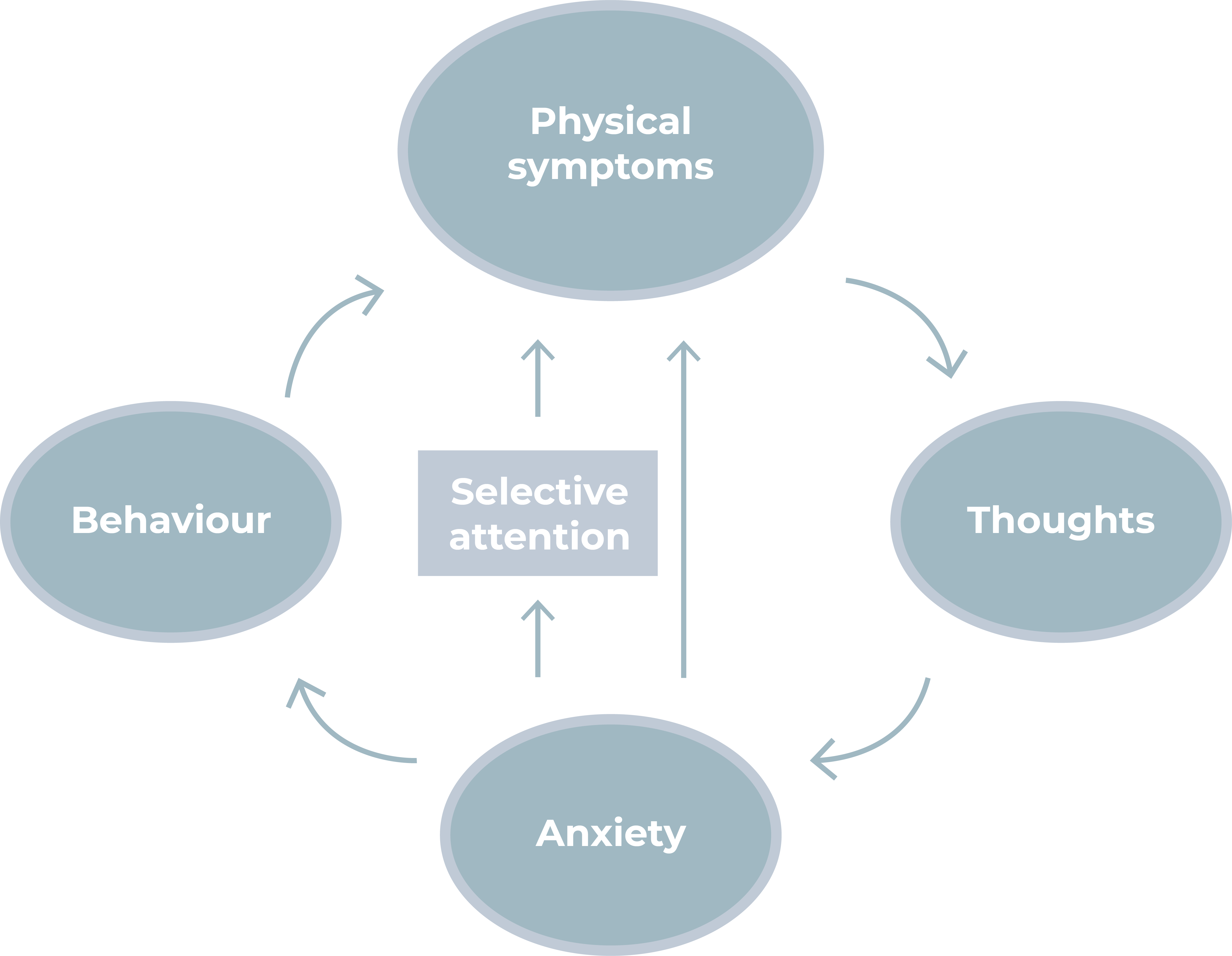

Often, there is a vicious circle of anxiety, existing of several factors that sustain the fear of an illness:

- Physical symptoms (with or without a medical explanation), for example chest pain that is interpreted from an anxious perspective.

- Negative thoughts can arise due to this interpretation, causing feelings (fear).

- This fear causes physical reactions (such as palpitations, stomach complaints, dizziness and muscle tension). Anxiety can also cause you to focus on these physical sensations even more.

- In response, you look for ways (behaviour) to reduce your anxiety, such as avoiding certain things or asking confirmation from loved ones or doctors.

Therapy

This vicious circle of anxiety sustains the symptoms. During the treatment, you will find ways to break this circle. Thoughts and behaviour are targeted as starting points for the treatment.

Treatment with Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) has been scientifically proven to be effective. The treatment aims to reduce the anxiety and over-anxiety caused by the physical sensations. The aim is not to reduce physical complaints or to exclude diseases, but to ease concerns about them. Instead, it examines the relationship between the thoughts that automatically arise and the emotions that you feel when you experience the fear of illness.

An important concept is the assumption that not only the physical phenomena cause the anxiety, but also the thoughts you have about them. In addition to your automatic thoughts, your behaviour will be observed.

With the help of cognitive therapy, we will try to detect, investigate and challenge these automatic thoughts. We challenge these thoughts with the help of a thought record. You will also be challenged to change your behaviour, for example, with the help of behavioural experiments.

Source:

Keijsers, G. P. J., Van Minnen, A., Verbraak, M., Hoogduin, C. A. L. & Emmelkamp, P., (2017). Protocollaire behandelingen voor volwassenen met psychische klachten.