Before completing the treatment, we will discuss identifying and preventing similar complaints in the future.

Experiencing complaints again is normal, so see this as a reassurance plan. Fortunately, experiencing complaints again does not mean that you are back to square one, it can actually help you to see that something is going on and inform you on how to intervene before you relapse.

To ensure that your complaints do not worsen, it is important to be able to identify when you are feeling low or when you begin to revert back to old patterns early on, so that you can intervene in time. This document can help you with this and help you create a relapse prevention plan or reassurance plan.

It consists of three steps:

Identifying, repeating and seeking support. It is advised to regularly read this form after completing your treatment and keep it nearby.

Step 1) Signals and risk situations

It is important that you can identify or recognize when you are feeling low. Some people notice this in their bodies, others notice this in their behaviour.

What signals are you aware of that indicate that you aren't feeling well?

We can subdivide these signals into:

- physical signals: e.g., back pain, headache, lethargy

- psychological signals: e.g., worrying, concentration problems, negative thoughts

- behavioural signals: e.g., sleeping badly, withdrawing, no longer exercising, drinking more alcohol, working too hard, getting angry faster

Fill in the list below. Think back to the period leading up to the complaints. Describe the signals as concretely as possible. Examples of this are: "Lying awake in bed for more than an hour a day for a week" or "Coming home from work exhausted for two weeks’’.

Physical signals:

___________________________ ___________________________

___________________________ ___________________________

___________________________ ___________________________

Psychological signals:

___________________________ ___________________________

___________________________ ___________________________

___________________________ ___________________________

Behavioural signals:

___________________________ ___________________________

___________________________ ___________________________

___________________________ ___________________________

Risk situations

In addition to recognizing signals, it is also important to recognize circumstances that can increase the risk of a relapse, so-called ‘risk situations’.

Examples are: busy weeks at work, arguing with family, conflicts at work, moving to a new house, having to work night shifts, ending a relationship, disappointment, etc. Based on the presence of risk situations, you can decide if extra interventions to prevent relapse are needed. Describe the risk situations that are relevant to you.

______________________________________________________

______________________________________________________

______________________________________________________

______________________________________________________

______________________________________________________

Step 2) Practising what you have learned

People learn through practice, such as learning how to ride a bicycle or learning how to skate, which probably started as trial and error, but eventually got better and better! It is therefore very useful to repeat the most useful elements of the treatment by writing them down below. We use the terms ‘pitfalls’ and ‘tools’.

Pitfalls

Pitfalls are thoughts that are or behaviour that is not helpful, but that you tend to rely upon when you are feeling unwell. These are, for example, thoughts such as "I am not important" or behaviour such as withdrawing instead of seeking support.

Enter below what you tend to think when you are not doing well and how you are inclined to behave when you are not doing well.

Pitfalls - Thoughts or Beliefs

___________________________ ___________________________

___________________________ ___________________________

___________________________ ___________________________

___________________________ ___________________________

Pitfalls - Behaviour

___________________________ ___________________________

___________________________ ___________________________

___________________________ ___________________________

___________________________ ___________________________

Tools

Tools are ways, methods or techniques that you can use to deal with difficult situations or thoughts. Think of everything you have learned during your treatment, but also of things that you have discovered and experienced as helpful during this recent period. Write them down below.

Some examples are comforting yourself, talking to others, challenging thoughts with a thought record, anti-anxiety exercises, relaxation techniques, rest, exercise, etc.

Tools - That help me when I'm having a hard time

___________________________ ___________________________

___________________________ ___________________________

___________________________ ___________________________

___________________________ ___________________________

___________________________ ___________________________

___________________________ ___________________________

Step 3) Get support or help

During the treatment process, you may be able to recognize the individuals who can help you when you are feeling down. Write down below who these people are and what they can do for you. For example: someone with whom you can talk, someone with whom you can laugh, someone who can motivate you, someone who does not judge you, etc.

Who What can this person do for me?

______________ ______________________________________

______________ ______________________________________

______________ ______________________________________

______________ ______________________________________

______________ ______________________________________

Rounding off

Do you have any extra motivational or helpful words for yourself? Think of a saying, a quote that gives you courage or that you find inspiring, or a short letter to yourself.

Write this down below:

______________________________________________________

______________________________________________________

______________________________________________________

______________________________________________________

______________________________________________________

______________________________________________________

______________________________________________________

______________________________________________________

A part of social anxiety treatment is to practice giving presentations. Having to give a presentation often entails a lot of tension and it can be useful to learn how to cope with this. Often, you will notice that your attention is focused on yourself and that you perform safety behaviour. In addition, you can have negative expectations and catastrophic thoughts. For these reasons, it can be helpful to practice giving presentations during social anxiety treatment. It will help you to obtain a more realistic outlook of your presentation. Your professional will always discuss this exercise with you.

Instruction presentation

- You are going to give a three-minute presentation, for example, about the social anxiety model. During this presentation, you will explain how social anxiety works and provide examples from your own life.

- For the presentation, you will come up with a personal goal: for example, to reduce the use of safety behaviour or to show more open behaviour, such as making eye contact, smiling, using body language, or paying attention to the other. With the help of your professional, you will make this goal as concrete as possible. For example, a concrete goal would be ‘Don’t touch my hair during the presentation’, rather than ‘Leave a good impression’.

- Before you start presenting, do thirty seconds of attention training. Start off by focusing on yourself and your anxiety symptoms, then on the environment in which you will give a description of your environment. Finally, you will focus your attention on the content of the presentation and then summarize it.

- You will use recording equipment to film yourself (for example, use your partner’s phone, an old phone, a digital camera or the camera on your laptop).

- Your professional will keep track of the time.

What was it like to give the presentation? What do you see when you look back at the recording of yourself?

Source:

Keijsers, G. P. J., Van Minnen, A., Verbraak, M., Hoogduin, C. A. L. & Emmelkamp, P., (2017). Protocollaire behandelingen voor volwassenen met psychische klachten.

Concentration is the capacity to control your attention so that you can focus on one task, object or thought. Being able to direct your attention is therefore important to be able to concentrate properly and prevent you from getting distracted too easily.

If you are dealing with social anxiety, you may have noticed that your attention is often focused on yourself and the surrounding environment rather than the task at hand. As a result, your task performance can deteriorate, which, in turn, can make you more insecure next time.

You can compare this, for example, to a basketball player who is not able to perform optimally when he/she puts too much focus on things in his/her environment. The goal is to play the ball into the basket and not to pay attention to the audience, how he/she looks, or how much stress he/she feels. If the basketball player pays too much attention to the environment, chances are that he/she will not be able to get the ball in the basket and, therefore, will not perform the task properly. As a result, they will feel more unsure about whether it will go well the next time.

Exercise

Concentration is a skill. This means that you can improve your concentration. You can do this by doing task concentration exercises.

In task concentration exercises, the goal is to learn to focus as much attention as possible on the task instead of on irrelevant things. During these exercises, you will deliberately divide your attention between the task, yourself and the environment.

Listening exercise 1: you and your professional cannot see each other

- The professional will tell a story.

- Try to concentrate on listening.

- Summarize the story.

- Give an indication (a percentage) of how concentrated you were on yourself, the task and the environment.

- Give an indication (a percentage) of how successful the summarization was.

Listening exercise 2: you and your professional can see each other

- Listen to the professional’s story again.

- Try to concentrate on listening.

- Summarize the story.

- Give an indication (a percentage) of how concentrated you were on yourself, the task and the environment.

- Give an indication (a percentage) of how successful the summarization was.

Listening exercise 3

- Listen to a new story told by the professional.

- Try to listen as best as you can and try to focus your attention on yourself and/or think about blushing, trembling or sweating.

- Summarize the story.

- Give an indication (a percentage) of how concentrated you were on yourself, the task and the environment.

- Give an indication (a percentage) of how successful the summarization was.

Listening exercise 4

- Listen to a new story told by the practitioner.

- Try to listen as best as you can and try to focus your attention on yourself, or think about blushing, trembling or sweating but continuously redirect your attention back to the task.

- Summarize the story.

- Give an indication (a percentage) of how concentrated you were on yourself, the task and the environment.

- Give an indication (a percentage) of how successful the summarization was.

Listening exercise 5

- Listen to a new story told by the practitioner. This story will include something about self-centeredness.

- Try to listen to as best as you can.

- Summarize the story.

- Give an indication (a percentage) of how concentrated you were on yourself, the task and the environment.

- Give an indication (a percentage) of how successful the summarization was.

Sources:

Keijsers, G. P. J., Van Minnen, A., Verbraak, M., Hoogduin, C. A. L. & Emmelkamp, P., (2017). Protocollaire behandelingen voor volwassenen met psychische klachten.

During your treatment for social anxiety, you can practice with social situations. By doing this, you can learn new skills and gain new insights. You will practice together with your professional by means of a role play. In this role play, you will act out a situation that makes you feel anxious.

During the session, your professional will explain the role plays to you.

Source: Keijsers, G. P. J., Van Minnen, A., Verbraak, M., Hoogduin, C. A. L. & Emmelkamp, P., (2017). Protocollaire behandelingen voor volwassenen met psychische klachten.

When you suffer from illness anxiety (also known as hypochondria), you are afraid that you have a serious illness. Physical symptoms, whether they can be medically explained or not, are interpreted from an anxious perspective.

If you feel something weird in your body and are afraid that you might have a serious illness, it can cause you to feel a lot of tension. When experiencing heart palpitations, stomach complaints, muscle tension or fatigue, for example. These physical complaints lead to even more attention being focused on the anxiety of having a serious illness. This unpleasant feeling causes you to perform anxiety-reducing behaviour: you will try to find ways to get rid of the anxiety as quickly as possible. For example, you might avoid certain situations or do research on your symptoms. You might also use safety behaviour. This behaviour also influences your physical symptoms in the short and long term. Consider, for example, the deterioration of your physical fitness by avoiding exercise or the development of spots or bumps due to continuously touching a certain body part or area.

With the help of your professional, you will list your cognitions (thoughts and thinking styles) and behaviour associated with the illness anxiety disorder to gain more insight into your anxiety.

Examples of Illness Anxiety thinking styles:

- Mental filter: Using only one situation and ignoring others to reach a conclusion. For example: I am having heart palpitations, which must mean I am having a heart attack.

- Overgeneralization: Drawing general conclusions based on one fact. For example: No one understands me.

- Jumping to conclusions: Drawing conclusions based on arbitrary assumptions. For example: If I feel sick, everyone will think I’m ridiculous.

- Catastrophizing: Assuming the worst-case scenario will materialize. For example: If I have heart palpitations, I will have a heart attack and die.

- Personalization: incorrectly relating situations to yourself. For example: The chance of getting a brain tumour is small, but it will happen to me.

- Probability overestimation: Overestimating the probability that something will occur. For example: If I feel something unusual in my body, it is 100% a sign of a serious illness.

- Magical thinking: Believing that thoughts and ideas eventually lead to actual situations. For example: If I think about cancer, I will get it as well.

Examples of thoughts:

- I must be absolutely sure that this phenomenon is not dangerous.

- Only someone else can reassure me.

- If I feel something weird in my body, it is a sign of a serious illness.

- I am 100% sure what this physical symptom means.

- When I’m healthy, I shouldn’t feel anything unusual in my body.

- If I’m worried about a serious illness, I will end up getting it.

Examples of illness anxiety (safety) behaviour:

- Seeking reassurance by going to the doctor.

- Control behaviour, such as touching or visually inspecting the body, checking bowel movements, searching for information on the Internet.

- Avoidance behaviour, where you avoid certain activities. Consider, for example, avoiding certain foods, sports, social interactions or TV programs.

Source:

Keijsers, G. P. J., Van Minnen, A., Verbraak, M., Hoogduin, C. A. L. & Emmelkamp, P., (2017). Protocollaire behandelingen voor volwassenen met psychische klachten.

What is grief?

Grief is the emotional experience one goes through after loss. It is usually associated with the loss of a loved one but can also occur after a loss of any kind. For example, after a divorce, loss of a job, or a terminal diagnosis. First off, it is important to realize that the process of grief and the time it takes to go through this process is very different for each individual. Research on grief has shown that there are 4 typical experiences while processing grief. Not everyone who experiences grief will experience all these components or experience them to the same intensity:

- Separation Distress. This results in a range of emotions such as sadness, anxiety, anger, pain, loneliness, etc.

- Traumatic Distress. This is associated with feelings of unreality, disbelief, shock, and avoidance of emotional triggers.

- Feelings of guilt and regret.

- Social withdrawal.

Later on in the grieving process, as the pain subsides, feelings of acceptance and understanding tend to arise. This is when the person will begin to experience more positive emotions, accept the circumstances and often derive some meaning from the loss. The grief still remains but it no longer affects their daily functioning. Some people experience more intense grief that instead gets worse over time and affects their functioning for a long period of time; this is called complicated grief.

What does someone dealing with grief experience?

The experience of grief is vastly different for each individual, both in intensity and length of time. The individual can experience a large range of emotions, such as the ones described above; sadness, anger, guilt, disbelief, regret, etc. That can be overwhelming at first. They may have difficulty accepting the loss or experience a feeling of meaninglessness or detachment. They also may find it difficult to function normally, for example when going to work or carrying on with their daily life. They may socially withdraw from their friends and family or begin to avoid things that remind them of the loss. Some people may even feel numb and ‘emotionless’. Many people also have symptoms of depression, especially if they suffer from long-lasting, ‘complicated grief’. This can include symptoms such as a consistently negative mood, sleeping problems, a change in appetite, fatigue and lack of motivation.

What can you do to help?

- Be empathetic and listen compassionately. Someone grieving is going through a lot and is probably experiencing a wide range of emotions. They may not be able to function properly and perform to their usual standards. In this case, it can help to be sympathetic and understanding, and support them in a non-judgmental way.

- Give them support. Try to be warm and patient. Check in on them occasionally to see how they are doing and be there when they need it most. It can be good to plan days out or things to do with them and encourage them to remain active. However, it is important that you don’t push them into doing things they don’t want to do.

- Accept the other’s experience. Let them know it’s okay to feel the way they do.

- Be careful when giving advice. It is important to be careful when giving advice, because you don’t want to give them the impression that you dismiss their feeling of guilt or loss. Instead, acknowledge their emotions and experience.

- Don’t avoid the topic. It can aid the process to talk about their loss and what they are experiencing. Ask them how they feel occasionally. It can also be helpful to encourage them to remember some positive memories, too.

- Don’t overthink it. Just being there to support them and as someone to talk to who listens is often enough. Your presence and support are already a great help and source of comfort!

- Offer help. Offer help for small things that can ease the burden of daily life, such as administration processes regarding the loss, or grocery shopping or taking on house chores. This can help them find some time to focus and process the loss.

- Communicate about their needs. If you are feeling unsure, ask them how they want to be supported and helped, then you know what their needs are and how best to help them.

- Be patient. The process takes a varying amount of time for everyone, try not to pressure them to move on, this can hinder the process.

Take care of yourself!

Be careful not to overburden yourself when caring for another. Be there to support them, but also make sure that you get plenty of rest and relaxation, too. It can be a long, tough process, and the emotions they experience can be quite intense to be around. Make sure you find some space for yourself and, if it becomes overwhelming, don’t hesitate to seek (professional) support yourself.

Sources:

When you worry a lot, it is important to examine the underlying beliefs or thoughts you have about worrying. These are the beliefs you have about your own thinking, instead of about the content of your worrying thoughts.

Examples are: “Help, all this worrying is really going to drive me crazy!” or “All this worrying can’t be good for my heart“.

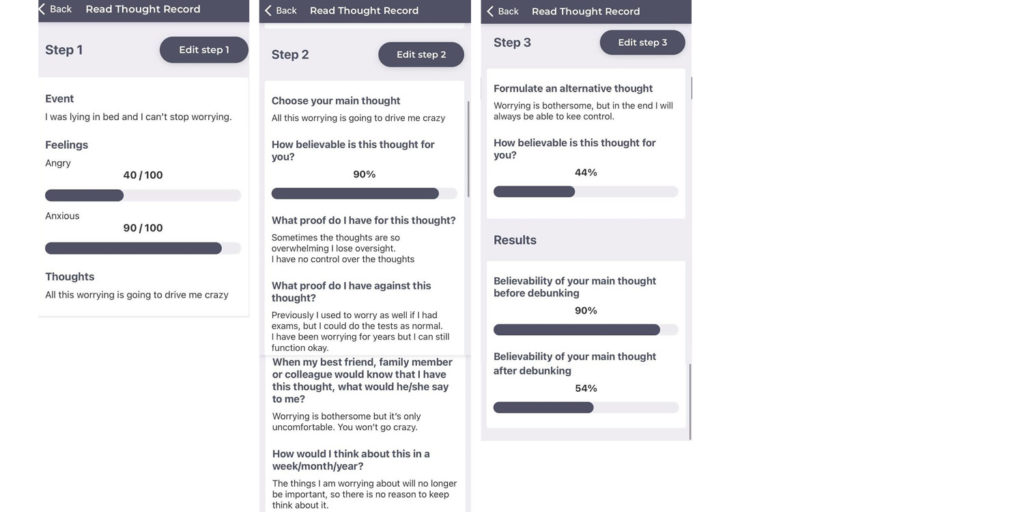

To investigate your beliefs about worrying, you can fill in a Thought Record (Thought records are available in the NiceDay app):

- Step 1: Describe the moment during which you are worrying, fill out your feelings and, in the section ‘Thoughts’, fill out your thoughts and beliefs about the worrying.

- Step 2: For the main thought, choose the thought or belief that you want to explore. If you have multiple thoughts or beliefs, you can use a new Thought Record for each belief, and then skip ahead to the questions that you want to answer. For this exercise, you will at least answer questions 1a and 1b. In doing so, you can write down arguments that support or contradict your belief about worrying. You can also use the questions 2 to 7 to help you with this.

- Step 3: Enter an alternative balanced belief here. This is a belief that may be more realistic than the old belief you held.

Below, you can find a completed example:

Questions: Arguments that contradict the beliefs about worrying

Write down arguments or experiences that prove that your opinion is not (completely) valid. You can use these questions to help you with this:

- What arguments contradict your belief about worrying? Have you had experiences that prove that your opinion is not always or not completely correct? What indications are there that prove that your belief about worrying is incorrect?

- Is there someone whose opinion you value a lot? There might be several people. What arguments would they make that contradict your view of worrying? And what do you think of these arguments?

- Suppose someone from your family or circle of friends shares your opinion about worrying, what would you say to him/her? Would you argue that their view may not be (entirely) valid? Would you say that to reassure them, or would you really mean it? And could you also apply these arguments to your own belief about worrying? Or do ‘other rules’ apply to you?

- If you had to appear in court, what evidence would you gather against your perspective on worrying?

- Suppose we travel twenty years ahead into the future and you are older and wiser. You are reflecting back on the beliefs you currently have about worrying. What arguments could you make against your beliefs about worrying?

- Are there people in your circle of family or friends who believe that your belief about worrying is incorrect? If so, for what reasons?

- If you are examining a negative belief, ask yourself: how many times in your life have you been worrying and how many times have the consequences you are worrying about actually proven valid? Rarely? What does that mean for your negative view of worrying?

- If you are investigating a positive belief, ask yourself the following questions: have there been situations in your life that you weren’t worried about? If yes, which ones? How did those situations unfold? If these situations also unfolded well, what does that mean for your positive belief of worrying?

Source:

Keijsers, G. P. J., Van Minnen, A., Verbraak, M., Hoogduin, C. A. L. & Emmelkamp, P., (2017). Protocollaire behandelingen voor volwassenen met psychische klachten.

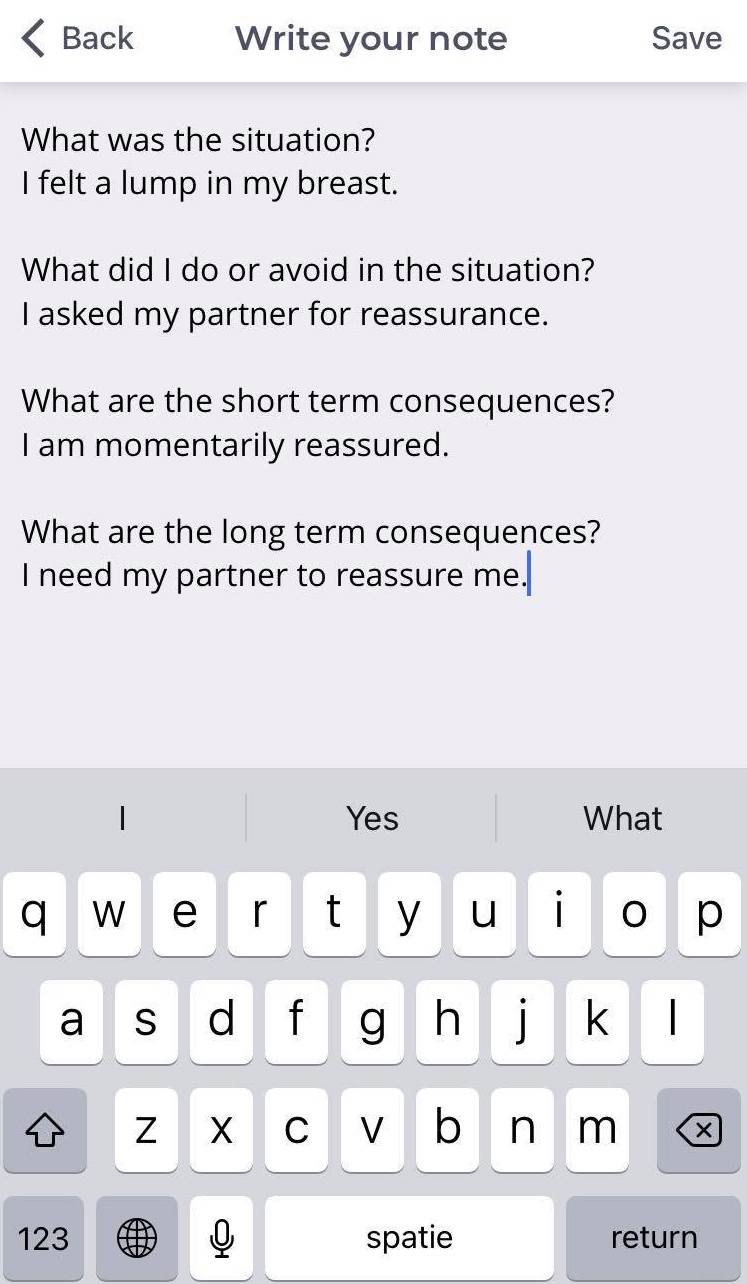

When you suffer from illness anxiety, you will often try to reduce your anxiety as quickly as possible, for example by displaying/avoiding certain behaviour or seeking out / avoiding situations. This, in turn, affects your anxiety and your physical symptoms. It can help to gain insight into these kinds of behaviour.

You can write about the situations you find difficult.

What did you do or what did you not do, for example? What are the short- and long-term consequences of your behaviour?

Use the following questions and answer them:

- What was the situation like?

- What did I do or what did I avoid in the situation?

- What are the short-term consequences of this behaviour?

- What are the long-term consequences of this behaviour?

Source:

Keijsers, G. P. J., Van Minnen, A., Verbraak, M., Hoogduin, C. A. L. & Emmelkamp, P., (2017). Protocollaire behandelingen voor volwassenen met psychische klachten.

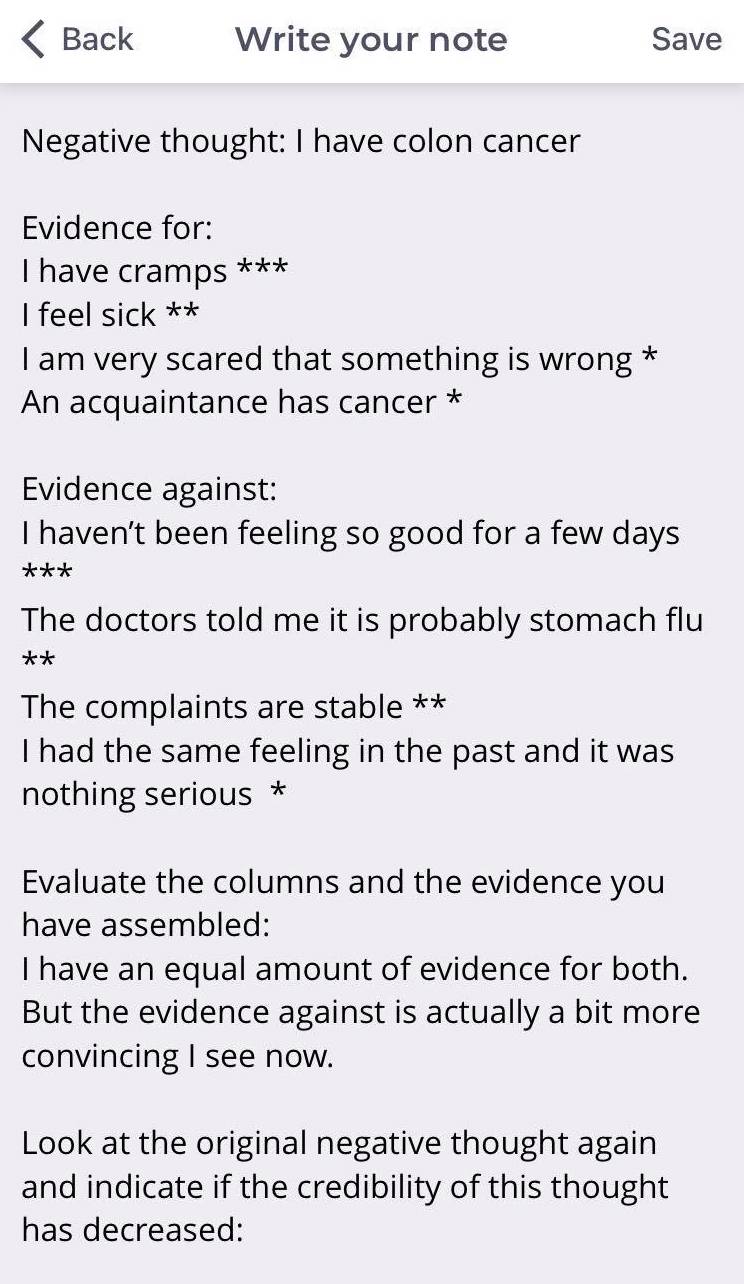

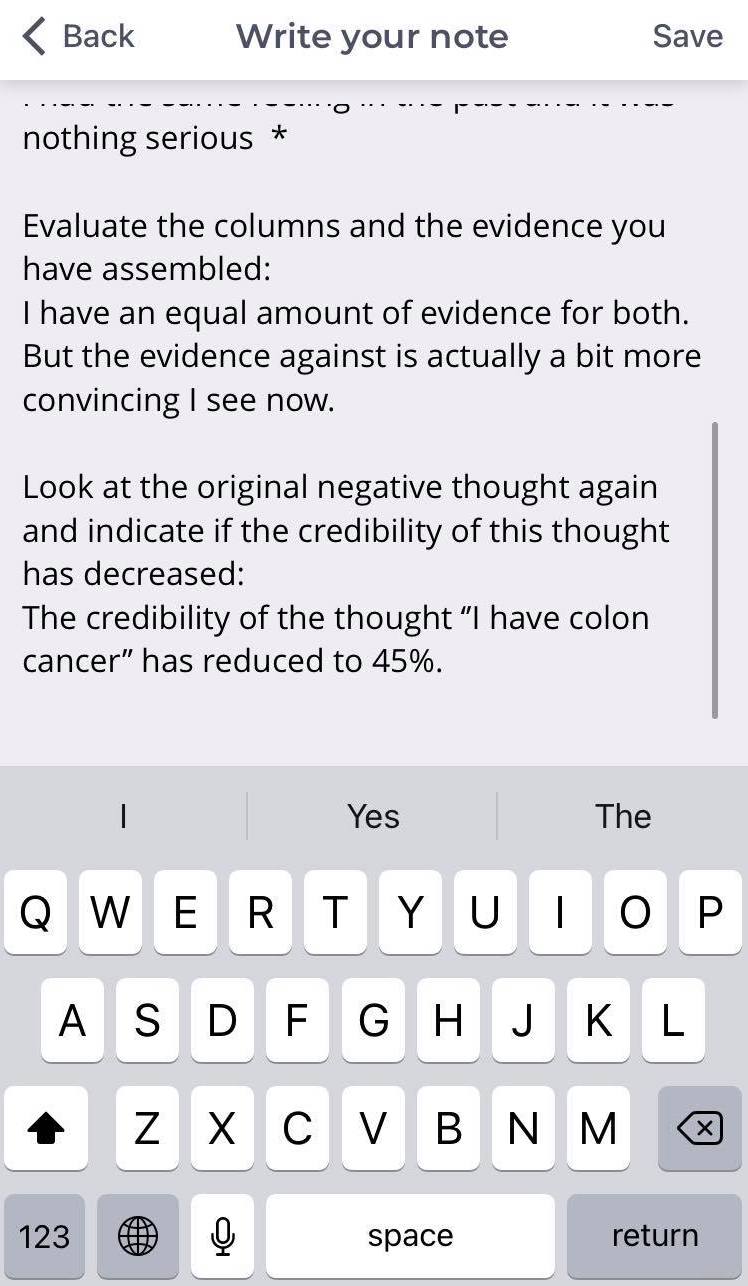

If you are bothered by specific negative thoughts, they can often feel like reality. For example, you may be convinced that you have a brain disorder or colon cancer. But are your own beliefs always correct? Using the two-column technique, you will line up evidence both for and against the negative thought or belief to examine whether your belief is correct.

Two-column technique:

- Step 1: First of all, it is important to investigate which thought or belief you want to challenge. Write down this belief. Assign a percentage to how credible you find the belief. For example: I have colon cancer. The credibility is 90%.

- Step 2: Write down the headings ‘Evidence pro and ‘Evidence con’.

- Step 3: Come up with evidence both for and against the belief and write all of it down.

- Step 4: Have you written down all the evidence? Determine how much weight each piece of evidence has by using asterisks (*, ** or ***); the more asterisks, the heavier the evidence. For example: I have cramps ***.

- Step 5: Evaluate the columns and evidence you have collected. What is your perspective now? What is the ratio of pro evidence and con evidence?

- Step 6: Review the original negative belief and indicate whether the credibility of this belief has dropped. For example: I have colon cancer. The credibility has dropped to 45%.

- Step 7: Finally, you can further challenge your thoughts (for example, with the help of a Thought Record) and come up with less unpleasant and less catastrophic thoughts. Of course, you can also choose to further challenge this with the help of your professional.

Source:

Keijsers, G. P. J., Van Minnen, A., Verbraak, M., Hoogduin, C. A. L. & Emmelkamp, P., (2017). Protocollaire behandelingen voor volwassenen met psychische klachten.

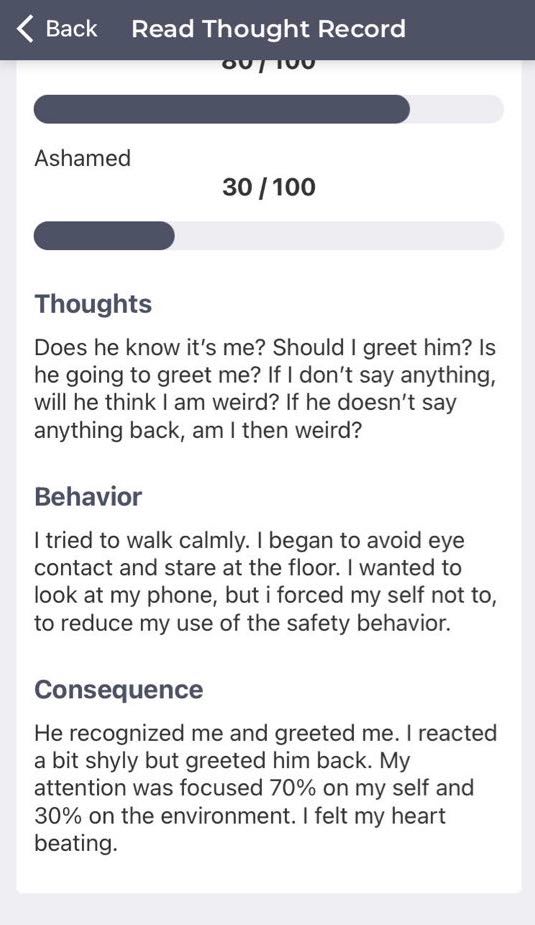

When social situations cause you to feel stress, it is important to practice with them in the right way.

By writing down and describing these social situations, you can investigate what went well and what went wrong. By reflecting on them, you can learn whether you can manage the situations in a different way next time. You can describe the social situations and your reaction to them.

You can do this as follows:

- Event: Describe the situation. What happened exactly?

- Feeling: How do you feel and how strong is this feeling? Choose one or more feelings: happy, angry, scared, sad, ashamed, etc.

- Thoughts: Describe your automatic thoughts. For example, what were you afraid of? What were you thinking of?

- Behaviour: What did you do? How did you react? Did you rely on safety behaviour or open behaviour?

- Consequence: What did the situation result in? What was your attention focused on? Which physical sensations did you experience?

Source:

Keijsers, G. P. J., Van Minnen, A., Verbraak, M., Hoogduin, C. A. L. & Emmelkamp, P., (2017). Protocollaire behandelingen voor volwassenen met psychische klachten.