Assuming you have already thought about what you want to change regarding your addiction and usage, the next step is to figure out HOW you can make that happen. The HOW is perhaps the most important step in making change effective and easier. The importance of thinking about these measures can best be illustrated by giving proper examples.

Examples:

If you want to start exercising more: Do you plan to go running? Make sure you have all your stuff ready in preparation the night before you want to go on a run. If you can put on your workout gear without obstacles, you will make it easier on yourself to start your run if you plan to go after a long day of work.

If you want to drink more water: Ensure that you always have a bottle of water nearby (in the car, in your bag) and find ways to remind yourself. By doing this, you will be regularly reminded to drink water in all kinds of ways, instead of trying your best not to forget, which will help you develop your new habit faster.

What can help you?

Quitting or reducing your usage is not only a matter of persevering or trying harder (although it can sometimes come down to that), but instead often comes down to carefully considering what will work best for you and what tools you are going to need to make the change.

Of course, in the beginning, you will have to consciously approach things differently to prevent yourself from going on ‘autopilot’ (and all the associated consequences). The longer you try doing so, the more you’ll notice that it becomes increasingly easy to do things differently instead of relying on the same patterns every day.

Because your addiction and usage have become a pattern, it is usually quite easy to think about when it’s going to be difficult and set up a plan in advance for this.

The abbreviation HALT (Hungry, Angry, Lonely, Tired) can help you to think about difficult moments in advance. You can read more about HALT here.

Below, we differentiate between 3 different types of self-control measures. They are listed with a brief explanation and some examples to give you some food for thought.

1. Avoidance

Why are you going to make it difficult for yourself when you can also make it easier? Think about the things you can avoid that contribute to the habit you want to quit. You can do this in several ways:

- Not having any alcohol in the house takes away a lot of the temptation.

- If you want to drink a maximum of 2 units per evening, make sure you only have a maximum of 2 units at home.

- Buy (or order!) groceries for the whole week so that you are not tempted to go to the supermarket.

- Start cooking earlier or later.

- Be very cautious of parties, birthdays, etc., especially in the first few weeks. If you think they are going to be too difficult, postpone them until you are more used to your new pattern.

2. Alternatives

Thinking about what you don’t want is easy. But what do you want? If you’ve decided to tackle your usage, that is important to think about. Alternatives can also be interpreted broadly in this case.

- What are you going to drink if you’re not drinking alcohol? Make sure you have enough different alternatives at home, since having options makes it easier.

- What are you going to do with the time that you have left over? Make sure you think in advance about what you DO want to do instead (e.g., take a walk, take a shower and go to bed early, visit (safe!) friends or family).

Tip: use the NiceDay app to create reminders that can give you motivation at the right time and a message of support during the most difficult moments. After all, you know exactly what you need during these moments. For example:

- Daily at 7:30 PM: “Go for a short walk; whether you feel like it or not, it helps!”

- A birthday you want/need to go to at 8:00 PM: ”Start with a 0%, then take a fizzy water followed by a Coca-Cola”

- Weekly shopping every Saturday at 11:00 am: “Buy tasty alternatives instead of alcoholic drinks”

- Daily at 5:30 pm: “Go cook so you don’t feel like having a drink”

3. Reward and Reward Alternative

Reward

Many people find rewarding themselves difficult, but it’s important to think about what you can do to reward yourself after, for example, sticking to your plan for a week. Maybe buy yourself a bunch of flowers, sleep in or buy yourself something you’ve wanted for a while? Anything that can help to reinforce the feeling that you’re doing a good job can be a reward. Read more about rewarding yourself here and get some inspiration about how you can reward yourself here.

Reward alternative

What are you going to do if you unexpectedly don’t quite manage to stick to your plan? Often, this is accompanied by a feeling of shame or perhaps failure. This feeling only increases the risk of further slipping. Something that can help in these situations is an ‘alternative reward’. These are small tasks that you can do in these moments, which help you to feel good about yourself again (¨at least I did that well¨), which reduces the risk of relapse.

Make sure you don’t list tasks that are too strenuous (go for ‘clean the coffee machine’ rather than ‘scrub the whole kitchen’) so that it doesn’t feel like a punishment (which will make you feel worse, which is not the objective). Therefore, go for small tasks which provide relief and make you feel good.

You can write about your alternative reward.

Sources:

Merkx, Maarten J.M. (2014). Individuele cognitieve gedragstherapie bij middelengebruik en gokken. Utrecht, Nederland: Perspectief Uitgevers.

What is burnout?

Burnout is the exhaustion of the body and mind due to a long period (years) of high work pressure or stressful (work) conditions. An example of this could be high demands at work, insufficient coordination between person and work or persistent tension in the workplace. Perfectionists or ambitious people are especially at risk of becoming burned out. Similar complaints can also arise in other stressful situations that have nothing to do with work, when there are long-term relationship or family problems, for example.

How does someone with work stress or burnout feel?

People with burnout can either feel overtired and hyperactive or just (over)tired. The stress system becomes hypersensitive to stress and, therefore, tries to suppress it more actively. The stress system is thus overactive in being stressed but also in trying to suppress it. As a result, the person feels less alert, is not able to cope as well with stress as before and is more tired. A common symptom of burnout is having no energy to be active or to exert yourself. In addition, you may find it difficult to motivate yourself to do something about your situation and you can start to experience a low mood because of this. For that reason, burnout can also lead to depression. If you are experiencing burnout, it can be not easy to recover from that on your own.

What is it like being around someone going through a burnout?

It is not only the person going through burnout who suffers from his or her psychological complaints. It can also affect those in their nearby social circle, such as family members or partners. Life becomes more focused on the person with the psychological complaints than on the other(s) in the family. This can cause tension and cost those others energy. Because burnout has many consequences for the immediate social circle, it is important that the people in that circle are also involved in the treatment. You can read more about how you, as a loved one, can be involved in the recovery process of your partner or family member here.

What can you do as a friend or family member?

- Try to listen and be understanding when someone close to you expresses their burnout complaints. Someone with burnout has often had to deal with years of investment in work or other matters. Someone with burnout symptoms can experience intense emotions, such as anger, injustice and despair.

- Avoid trying to justify their complaints. It can mean a lot to someone just to be there to listen to them.

- Show that you have faith in them.

- Be aware of the small steps in their recovery. Recovering from burnout takes time and energy. A common phenomenon is that a lot of focus is placed on the end goal, while the steps in between are just as important.

- Whenever it costs you too much energy to offer support to someone experiencing burnout, it is time to call in (professional) help for yourself.

- Do fun things with them and stimulate their senses; go gardening, hiking, cooking and/or painting.

- Get outside: fresh air and exercise stimulate the production of mood-boosting neurotransmitters in the brain. It will do both you and your loved one good.

What should you avoid doing?

- Criticising or giving advice. This can make someone feel insecure.

- Pressuring them while they’re not ready yet.

- Explaining to the other person what is wrong with him/her or what he/she is doing wrong.

- Self-involvement: Don’t involve yourself in their behaviour or take his or her behaviour personally.

- Being judgemental: Telling your partner that they are taking too much on their plate can make the partner feel like he or she has failed.

Sources:

Keijsers, G. P. J., Van Minnen, A., Verbraak, M., Hoogduin, C. A. L. & Emmelkamp, P., (2017). Protocollaire behandelingen voor volwassenen met psychische klachten.

https://psycholoog.nl/behandelingen/tips-voor-naasten

Almost everyone who has suffered from a burnout has considered changing their work (environment) at some point. As a result of your complaints, you may have explored the possibility of finding another job and, therefore, a different future. It is important to think this through carefully before making an impulsive or thoughtless decision.

Returning to your current position

The first question is whether you want to return to your current position. You may prefer not to, or you may not have the confidence to apply again. It is important to solve existing problems so that you can be sure that quitting your current job is not an impulsive choice or the result of ‘flight’ behaviour. When you return to your current position, several problems may arise:

- You have difficulty with certain aspects of your position. For example, a high workload or unclear tasks.

- Certain working conditions limit your performance

- There are unresolved conflicts

- Your position has been lifted

- You have been transferred to a different workplace

- Your abilities and skills are insufficient for the position

- The content of your current position has changed

It is important to address and resolve the factors mentioned above, for example by setting priorities, planning breaks and guarding your own boundaries. Or by engaging a mediator to resolve conflicts.

Changing position within your current work environment or organization

You may be considering applying for a new job, but you also feel at home within the company you work for. Does your current position not provide you with the things you find important? In that case, it might be possible to change your position/function.

This can be handled in 4 ways:

- Find another similar position at the same level.

- Participate in internal training and relocate.

- Demotion (move from a higher position to a lower position).

- Promotion (move to a higher position with other, more challenging activities).

Leave your current work environment

There can be various reasons for leaving your current employer, e.g., because you are forced to leave or because you are fired after being on sick leave for a long period of time. Other reasons can include leaving voluntarily, outplacement (involuntary dismissal with a placement at another organization) or early retirement. In each case, you will have to deal with regulations and authorities. It is important that you are well aware of your rights and obligations, so that you are not faced with unpleasant surprises. Once this is all sorted out, you can focus on the following options:

- You are looking for a similar position at another company. If you enjoyed your job and it went well, this could be an option. An advantage is that you are familiar in the field and can use your career network to find a new employer.

- You are looking for a different kind of job. If so, it is important to know what you are capable of and where your skills lie. This can be done with the help of your therapist or with an outplacement process. The Institute for Employee Benefit Schemes (UWV) also offers these types of programs.

- You start your own business. This requires the right preparation but can certainly be a good way to put some fun and excitement back into your work.

- You stop working. This is an option if you can make use of an early retirement scheme. If you retire, it is important to think about how you will fill your days.

Whichever path you choose, it’s good to get help making work-related choices. If you suffer from burnout, it is often necessary to examine your situation with the help of a coach, psychologist or other professional. By doing this, you will get a good understanding of your current situation, what you can expect and how you can deal with that.

Source:

Keijsers, G.P.J., Van Minnen, A., Verbraak, M., Hoogduin, C.A.L. & Emmelkamp, P. (2017). Protocollaire behandelingen voor volwassenen met psychische klachten.

In order to be happy at work, it is important that the working conditions and tasks match your motivations, preferences and skills. A good fit will result in more energy, pleasure and satisfaction. Therefore, it is useful to investigate to what extent your work energizes you. The following exercises can help you to do so.

Exercise 1: Energy balance

Create a table with two columns in which you rate each work task on how much energy it gives (energy gain) or costs (energy loss) you. You can do this on a scale from -10 to +10 and use ‘0’ to indicate a neutral effect. This will give you more insight into which tasks give you energy and which cost you energy. Below, you can find an example of such a table.

| Task | Energy loss or gain |

| Answering emails | -3 |

| Supervising interns | +6 |

| Making plans | 0 |

Exercise 2: Obstacles

There are many factors, other than work-related tasks, that can influence your energy, such as working conditions, personal characteristics or private circumstances. Make another table for these obstacles. You can find an example below.

| Obstacle | Energy loss |

| Annoying discussions with a colleague | -7 |

| Wanting to do everything perfectly | -3 |

| Combining work with raising children | -4 |

Exercise 3: Helpful resources

Opposite to obstacles are helpful resources. These have a positive effect on your energy. Make another table for helpful resources. You can find an example below.

| Helpful resources | Energy gain |

| Short commuting time | +3 |

| Friendly colleagues | +6 |

| Possibility to work from home | +4 |

Now, spread out all the tables next to each other. Is there anything that stands out or surprises you? What gives you the most energy? And what costs you the most energy? Is your energy balance in equilibrium? If not, what is causing the imbalance? Can you make a change? Below, you can find an explanation on how to tackle this.

Job crafting

Job crafting refers to making changes to align your work with your motivations, preferences and skills. There are a number of different strategies you can try. These are shown in the table below:

| Adjusting tasks | Adjusting relationships | Adjusting thoughts | Adjusting environment | |

| Add | Additional task: Adding a task that gives you energy. |

Working together: Collaborate on the task with others. |

Take a positive perspective:

Put more focus on the positive effects of the task for other people. |

Decorate:

Brighten up your work environment with decorations. |

|

Adjust |

Adjust the task:

Spend more time on (part of) a task that gives you energy. |

Different people:

Perform the same task with different people. |

Reinterpret:

Pay more attention to the positive aspects of the task. |

Re-locate:

Carry out your work in a different location or at a different time. |

|

Remove |

Remove the task: Spend less time on (part of) a task that costs you a lot of energy. |

Avoid: Avoid the people who cost you a lot of energy more often. |

Ignore Stop thinking about the unpleasant aspects of a task. |

Remodel:

Remove disturbing environmental factors. |

|

Solve |

Self-improvement Improve your skills through training and practice, making the task more enjoyable. |

Learning to cope with the situation: Learn to manage conflict. Improve social skills. |

Acceptance:

Accept that the task is part of the work and adjust your expectations. |

Alleviate:

Reduce discomfort in your workspace with the right equipment. |

Exercise 4: Adjustments at work

Pick a few of the energy-consuming tasks and difficult obstacles from the tables in exercise 1 and exercise 2. Write these down in the first column of a new table. In the second column, write down which job crafting strategy you want to apply. In the third column, specify how you are going to apply this strategy to the situation and write down the helpful resources you noted earlier in exercise 3 in the last column. An example of what this table might look like can be found below.

| Task/obstacle | Strategy | Plan | Helpful resource |

| Answering emails | Remove a task | Starting next week spend no longer than half an hour on emails in the morning | Come to an agreement with my supervisor on priorities |

| Meetings | Acceptance: Accept that meetings are part of the job |

No longer complain about the length of the meetings | |

| Annoying discussions with a colleague | Learn to cope or avoid | Improve social skills and engage in conversation with them. Or approach the colleague less often. | Talk to other colleagues about how they deal with this |

| Wanting to do everything perfectly | Remove | Lower expectations | Compare myself to colleagues who are less careful. |

Source:

Keijsers, G.P.J., Van Minnen, A., Verbraak, M., Hoogduin, C.A.L. & Emmelkamp, P. (2017). Protocollaire behandelingen voor volwassenen met psychische klachten.

Time management is not easy and can take a lot of practice to get good at. Below, you can find some tips to help you with your time management.

- Try to become aware of when you are procrastinating and what your reasons for procrastinating are. Think about which part of the task is stopping you from making a start now. Be especially mindful of putting off difficult, high-priority tasks.

- Try to focus on one task at a time. By always trying to multitask, you constantly have to switch between tasks quickly. This can be very stressful, and tasks will take longer to complete. Do you need to set aside a task for a while because you have something important to do? Then make sure to leave yourself a reminder so you know exactly where you left off when you get back to it.

- Plan enough daily rest breaks. For example, in addition to your lunch break, plan in 10-minute coffee breaks alone or with a colleague.

- Take the time it takes to prepare and finish off the task into account. A work meeting can require a lot of preparation or extra tasks that have to be completed afterwards.

- Set boundaries for yourself. Determine your number of working hours per day and, for example, limit yourself to only working 30 minutes over time if necessary. Avoid working in the evenings or on weekends, as this will make it harder for you to get out of ‘work mode’. It might seem easy to quickly go through your emails, but it will keep your mind occupied with work for the rest of the evening. Take into consideration whether it is necessary to always be available.

- Find solutions for time-consuming daily tasks. See if there are possibilities to reduce or delegate daily administration, for example.

- Structure your work. This will reduce the time you spend looking for things. Ensure that your workplace is organized, store information in a structured way (in subfolders, for example), tidy up everything regularly by putting old documents in the trash and use a fixed layout for your computer screen.

- Choose to say ‘no’. Practice saying ‘no’ to tasks or explore why you are so prone to saying ‘yes’ to everything. Ask yourself or the other person how important the task is and decide whether you have time for the task, and, if so, when you can perform the task. A phone call may seem urgent, but sometimes it does not need to be resolved immediately. Do you struggle to say ‘no’ sometimes? Read more about assertiveness.

- Prepare for conversations and meetings in advance to make them more efficient. Be strict with the allocated time and set clear boundaries.

- It can be annoying when your work is constantly interrupted. Therefore, try to prevent distractions during tasks. When is it acceptable to be interrupted and when is it not? What can you do to resolve repetitive disruptions? Try turning off your email notifications, for example, or ask someone to come back later or set up fixed office hours. If it is urgent, give someone a maximum of 5 minutes, but be strict with the allocated time.

- It is impossible to properly remember all of your ongoing tasks, projects, instructions and conversations. Therefore, reduce the burden on your memory and ensure that you include important information in, for example, a report, so that you and others are able to quickly understand the information after reading it.

- Learn to delegate. In addition to reducing your own workload, you will learn to trust others or teach someone else how to perform the task. What are your reasons for not delegating something? Think about whether it is a valid reason (is it your favourite task? Maybe you are afraid to ask someone else?). Provide clear instructions and determine the degree of freedom. Do you want to be able to supervise someone closely, do you want an update now and then or would you like them to contact you if there are any problems?

- Organize your email efficiently. Use filters and special mailboxes to automatically organize all incoming e-mail traffic. This ensures that you can read the important and urgent emails first and the unimportant messages remain out of sight. You could also, for example, set fixed times with your colleagues in which they can and cannot email you.

Which tips are important for you to keep in mind? Write them down.

Source:

Keijsers, G. P. J., Van Minnen, A., Verbraak, M., Hoogduin, C. A. L. & Emmelkamp, P., (2017). Protocollaire behandelingen voor volwassenen met psychische klachten.

Time management is a way to experience more control over your time. This sense of control reduces stress, improves your health and improves performance. Therefore, a win-win!

Important components for time management are determining your work content and planning and prioritizing tasks. Below, you will find 4 exercises that can help you to do so.

Exercise 1: Time spent

Because it can be quite difficult to know how much time you spend on each task during a (work) day, it can help to keep track of which activities you spend time on and how important and urgent those activities are. You can use an Eisenhower Matrix to determine what you should prioritize. You can divide tasks according to urgency and importance. You can use the following matrix for work:

| Importance + | Importance – | |

| Urgency + | First task on to do list | Don’t do the task or pass it on to someone else |

| Urgency – | Plan in a time for the task | Don’t do the task at all and return it |

Keep track of what you spend time on during the week. Indicate how many minutes an activity took, what the activity entailed, and evaluate how important and urgent the activity was. You can also add an extra column in which you indicate whether the activity gave you energy (+) or cost you energy (-). You can find an example of such an overview below:

| Time | Activity | Important? | Urgent? | Energy |

| 08:00-08:15 | Check emails | + | – | – |

| 08:15-08:45 | Catch up with colleagues | – | – | +++ |

| 09:00-11:00 | Emergency meeting | ++ | +++ | – |

| 20:30-21:00 | Called a colleague about a forgotten email | + | + |

Based on your weekly overview, you can investigate whether you want to make changes to your planning. For example, by doing more tasks that give instead of cost you energy, or by using your time differently. You can also compare the total amount of time spent on an activity to the total amount of working time of the entire week. In this way, you can calculate how much time you spend on each activity and whether you think that’s appropriate.

Exercise 2: Estimating Time

Research has shown that people have a ‘planning fallacy’; we are optimistic planners, which means we underestimate the time required. By practicing planning your time, you will learn to make better estimates. You can do that in the following way.

Perform exercise 1 (again) and record the time spent on each activity, but, this time, start by estimating how much time you think you will need for each activity separately. Write down how much time you actually needed afterwards. Then, write down the possible reasons for needing more time than you expected, as well.

Was your estimate wrong?

- Did you not have the energy to carry out the activity according to your schedule?

- Did you miss information that prevented you from carrying out the activity according to plan?

- Were there people who kept you from the activity?

Afterwards, you can draw a conclusion about the planned time and the associated process. Maybe you needed more time, were distracted or maybe your colleagues, for example, did not provide the correct documents.

Exercise 3: Job position content

It is also important that the activities you do are appropriate for your position at work. Study an up-to-date description of your job position or look up specific work agreements and see if your current work matches this. There may be several options that you can then discuss with your manager:

- There is no current job description: You work according to informal agreements. It is wise to draw up a realistic job description yourself. Define the tasks you are expected to do and make a time estimate for them.

- The tasks performed correspond to your job description, but you are still short of time: Take note of which points of the description are unfeasible or unrealistic.

- The tasks performed do not match the job description: You do more than is asked of you. Consider why you are performing these tasks. Is that because of others or are you doing this on your own initiative?

- The tasks performed do not match the job description: You do less than is asked of you and do not perform certain tasks. Find out why this is the case.

Exercise 4: Planning

An important strategy for time management is systematic planning. You can do this as follows:

- Plan important things far in advance. Make a global plan for the coming year in which you include, for example, recurring milestones and/or important or busy periods. Then, make a monthly plan. In this, you can record appointments, tasks and reminders to put in your date planner.

- Make a to-do list. This is where you list all tasks that need to be done soon or in the near future, including any deadlines.

- Make a weekly schedule. Every Friday afternoon, take time to create a weekly schedule for the upcoming week in which you determine which activities you want to do on which day. You can make good use of a to-do list.

- Determine whether tasks are urgent or important.

- Divide larger tasks into subtasks and schedule them.

- Try to schedule no more than 60% of your tasks, leaving room for spontaneous tasks.

- Allow time for delays/setbacks. Keep 15 minutes free between each appointment, for example.

- Take your personal preferences into account. Some people want to start off calmly, while others are bursting with energy in the morning.

- Reserve the last 15 minutes of your working day to review tomorrow’s schedule.

These exercises may require some time investment; however, they will give you a lot of insight and probably save you time and energy in the long run.

Source:

Keijsers, G. P. J., Van Minnen, A., Verbraak, M., Hoogduin, C. A. L. & Emmelkamp, P., (2017). Protocollaire behandelingen voor volwassenen met psychische klachten.

To make your work reintegration as smooth as possible, it is important to make a clear step-by-step plan. It is unrealistic to simply continue from where you left off. Therefore, it is good to explore what best suits your current situation in consultation with your manager/supervisor. As preparation, you will look at the things that cause you stress and prepare for any obstacles. You can use the following step-by-step plan to help with your preparation.

Step 1. Drawing up the step-by-step plan

In this step, you will map out what you are going to need to take the first step. A few things to keep in mind:

- Is it necessary to change your position/function?

- Can you start in your own department?

- Which people can support you at work?

- Are there conflicts that require special attention?

In this exercise, you will assess all your work-related tasks based on pleasure, burden, time pressure and dependence on others. Give each task a score and write them down in each column. You can find an example below.

| Task | Pleasure | Burden | Time pressure | Dependence |

| Administration | 3 | 4 | 4 | 1 |

| Assessment conversation | 8 | 3 | 4 | 10 |

By using this table, you can see which tasks are more suitable to start with during the initial phase of your return to work at a glance. If there are other important criteria, you can add additional columns.

Step 2. Negotiate the step-by-step plan

Next, you will discuss the plan with your supervisor in order to come to concrete agreements about resuming your work. What activities are you going to perform, when, at what pace, in which department, in what time frame, how will the assessment work, etc.? In addition to your supervisor – who regularly evaluates your progress – a case manager with whom you can evaluate your performance can be appointed as well.

Step 3. Start and evaluation

Start with a few half-days per week and regularly ask your supervisor or company doctor for an evaluation. During the treatment, the intensity of symptoms/complaints are still monitored, work events are recorded, and obstacles and possible solutions are discussed.

Step 4. Build-up

You will have included the build-up in the step-by-step plan. With each following step, your complaints may temporarily increase. This is understandable and a normal part of the process. Therefore, it is not a reason to immediately make adjustments to the plan. Proper monitoring of complaints and a good progress evaluation are very important here. Try to make increases in work gradual and preferably spread them over smaller blocks over several days, rather than starting with one full working day. In addition to extending your working hours, you will also work towards carrying out a full range of tasks. This also means that you will gradually take on more complex and taxing tasks.

Step 5. Evaluation

Discuss and agree on arranging sufficient moments for evaluation in the long term. During these evaluations, you will monitor whether and when full resumption of work is feasible.

Source:

Keijsers, G. P. J., Van Minnen, A., Verbraak, M., Hoogduin, C. A. L. & Emmelkamp, P., (2017). Protocollaire behandelingen voor volwassenen met psychische klachten.

With the help of a thought record, you can keep track of your thoughts, feelings and behaviour. This will help you to discover and gain insight into your patterns. If you understand your thoughts, feelings and behaviour, it will be easier to change them.

You can answer the following questions:

- Event: Describe the moment in which you had an unpleasant feeling. What happened? Describe the event.

- Feeling: How do you feel and how strong is this feeling? This can often be felt physically (afraid, angry, sad, happy, ashamed).

- Thoughts: Describe the automatic thought(s) that preceded this feeling. What were your thoughts? What went on in your head, what did you say to yourself?

- Behaviour: What did you do? How did you react? What didn’t you do?

- Consequence: What consequence did this have? Describe the consequences of your behaviour.

Tip: A tip to learn to distinguish between thoughts and feelings is to be aware that thoughts occur in your head, while feelings are mostly physical. For example: ‘During the robbery, I thought I was going to die (thoughts), and I felt very scared (feelings).’

Below, you can find an example of a completed thought record:

| Event | Describe the moment you had the unpleasant feeling

I opened my email at work this morning and had 50 new emails. |

| Feeling | How do you feel and how strong is this feeling?

Angry 85%, Sad 75% |

| Thoughts | Describe the automatic thought(s) that preceded this feeling(s)

I am never going to finish this, I am not good enough. My colleagues are going to think I am a bad employee. |

| Behaviour | What did you do? How did you react?

The tension increased, my breathing was fast, and I found it difficult to concentrate. |

| Consequence | What consequences did this have?

I wanted to cry and go home immediately to get away from work. The anxiety and tension were so high that I almost had a panic attack. |

Thought record exercise

Think about a situation in which you had to deal with work stress or anxiety. Make sure this situation is tangible, for example: ‘I woke up yesterday and the thought of work gave me a lot of anxiety’. Use the thought record to walk through the situation. This video will explain how to properly complete a thought record.

The Thought record exercise is available in the NiceDay app.

Source:

Keijsers, G. P. J., Van Minnen, A., Verbraak, M., Hoogduin, C. A. L. & Emmelkamp, P., (2017). Protocollaire behandelingen voor volwassenen met psychische klachten.

Shame and guilt are common feelings for people experiencing a burnout. For example, you may feel ashamed about your complaints or feel guilty towards your employer or colleagues when you are not able to work. In this article, we will explain what shame and guilt are and to what extent they play a role in burnout.

Shame

Shame is an emotion you can experience when you feel embarrassed. It is a global negative self-evaluation. When you are ashamed of something, such as your burnout or certain symptoms that you are experiencing, there is a greater chance that you are less likely to talk about them or hide your symptoms from others.

When you hide your symptoms/complaints due to shame, others will not notice that you are feeling low. Therefore, they are not able to help you when you actually need it. As an example: you are feeling overwhelmed by all the tasks you have and you have lost your to-do list. In addition, you have to deal with approaching deadlines, and you have no idea how you are going to meet them. If you don’t talk about your situation because you feel ashamed, your colleagues will be less likely to offer help or ask how you are doing than when they are aware of your situation. Feelings of shame can actually ensure that your complaints are maintained or can even cause them to worsen.

Shame (unhealthy situation)

Shame (healthy situation)

Guilt

By guilt we mean the unpleasant feeling that arises as soon as you have done or not done something; when you think you have violated a moral standard, for example. Guilt is a negative assessment of specific behaviour.

When you feel guilty, this can automatically motivate you to improve/strengthen the bond with others, again, showing your commitment and sense of responsibility. But excessive or exaggerated levels of guilt can be disruptive and, in some cases, cause psychological and physical distress.

Guilt in the workplace

Feelings of guilt often arise after you have negative thoughts about yourself or others or after you have treated others negatively. Some people see their behaviour as a direct reflection of their self/functioning and do not see other factors that can also influence this (such as circumstances). Because of this, they blame themselves, because they think they are not doing their job well. As a result, they develop feelings of failure and loss of self-esteem. For example: a colleague has problems at home and therefore reacts bluntly, but you relate her reaction negatively to yourself, which reduces your self-esteem.

Furthermore, excessive guilt can leave you feeling like you’re falling short of others and not treating them warmly enough. This can make you want to overstate your interest in others. Then, you overcompensate, which makes you more prone to developing a burnout.

The more guilt you experience, the greater your chance of developing a burnout. You will put in more effort and overcompensate, which takes hard work and will cost you energy.

Guilt (unhealthy situation)

Guilt (healthy situation)

Sources:

Baumeister, R. F., Stillwell, A. M., & Heatherton, T. F. (1994). Guilt: an interpersonal approach. Psychological bulletin, 115(2), 243.

Maslach, C., & Jackson, S. E. (1985). The role of sex and family variables in burnout. Sex roles, 12(7-8), 837-851.

Olivares‐Faúndez, V. E., Gil‐Monte, P. R., & Figueiredo‐Ferraz, H. (2014). The mediating role of feelings of guilt in the relationship between burnout and the consumption of tobacco and alcohol. Japanese Psychological Research, 56(4), 340-348.

Pineles, S. L., Street, A. E., & Koenen, K. C. (2006). The differential relationships of shame–proneness and guilt–proneness to psychological and somatization symptoms. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 25(6), 688-704.

Price, D. M., & Murphy, P. A. (1984). Staff burnout in the perspective of grief theory. Death education, 8(1), 47-58.

Rabasa, B., Figueiredo-Ferraz, H., Gil-Monte, P. R., & Llorca-Pellicer, M. (2016). The role of guilt in the relationship between teacher’s job burnout syndrome and the inclination toward absenteeism. Revista de Psicodidáctica, 21(1), 103-119.

Tangney, J. P., Stuewig, J., & Mashek, D. J. (2007). Moral emotions and moral behavior. Rev. Psychol., 58, 345-372.

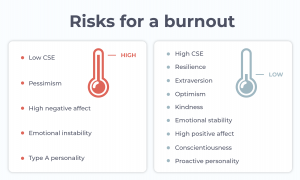

A burnout is the exhaustion of your body and mind due to a long period (years) of high work pressure or stressful (work) conditions. Not only do environmental factors play a role in the development of a burnout, individual factors, such as personality traits, can also play an important role in the development of a burnout.

Personality traits and risk of burnout

Research has shown that many personality traits are related to the three dimensions of burnout: emotional exhaustion, depersonalization and decreased personal performance. Emotional exhaustion refers to energy loss. Depersonalization refers to the development of a negative, cynical attitude towards others. Decreased personal performance is the tendency to judge one’s own work negatively.

Five Factor Model of Personality

A lot of the recent research on personality is based on the Five-Factor Model. This model divides personality traits into five different factors, which you can relate to the risk of developing a burnout.

Factor 1: Emotional stability

Emotional stability refers to the extent to which a person can cope with negative emotions, such as anxiety, hostility, frustration, and guilt, effectively. Research shows that emotionally stable people are less likely to develop a burnout. People with emotional instability are more likely to experience negative and anxious emotions and are more likely to be affected by them. They therefore run a greater risk of becoming burned out.

Factor 2: Extraversion

Extraversion refers to the extent to which someone is cheerful, sociable and enthusiastic. Extroverted people generally experience their work environment as positive because they often elicit positive reactions from colleagues. People who are extroverted are therefore more likely to describe their work environment as positive than people who are less extroverted. As a result, there is a smaller chance that they will be negatively influenced by their work environment, thus reducing the risk of a burnout.

Factor 3: Conscientiousness

Conscientiousness refers to the extent to which a person is performance-oriented, goal-oriented, organized and responsible. This results in less emotional exhaustion, less depersonalization, and a greater sense of professional confidence and personal competence. Conscientious people can manipulate their work environment in such a way that stressors decrease or disappear. They often employ problem-solving coping strategies. In addition, people with high conscientiousness often trigger positive reactions from colleagues. Conscientious people are less likely to give up and may have high expectations of themselves, but in general, someone who is conscientious is less likely to getting a burnout than someone who is less or not conscientious.

Factor 4: Kindness or altruism

Kindness refers to the degree to which a person cooperates, cares, trusts and is sympathetic to others. Kindness is positively related to personal ability and achievement and negatively to emotional exhaustion and depersonalisation. Kind people are often treated well because they treat others well. They may be more likely to receive social support and to trust people for help with their problems and are more cooperative. This can reduce feelings of cynicism and promote feelings of personal competence. People who have a kind personality may, therefore, be less prone to developing burnout.

Factor 5: Openness

Openness refers to the degree to which a person values authenticity, change and variation. People with this trait are imaginative, creative thinkers and are open to new experiences and ideas. They often use humour to deal with stress and are less likely to see situations as threatening but view them as a challenge. Openness has a positive relationship with personal competence, but the relationship between openness and burnout has never been proven. So, for the time being, we can say that openness has little or no relation to burnout.

Personality traits as predictors of burnout

In addition to the factors mentioned above, there are a number of personality traits that can be predictors for the development of a burnout. Namely:

- Core Self-Evaluation

Core Self-Evaluation (CSE) is about the fundamental belief in one’s own abilities and one’s belief in self-worth. CSE consists of four features:

- Self-confidence

- General belief in one’s own abilities (self-efficacy)

- Emotional stability

- The belief that you are in control (internal locus of control)

People with a high CSE see a difficult assignment as an opportunity to succeed because of their high self-confidence. People with a low CSE are more likely to see a difficult work assignment as threatening and stressful. They prefer routine work, for example. A low CSE is expected to be associated with a greater risk of developing a burnout.

- Positive affect and negative affect

Positive affect is the tendency to experience positive emotions, such as happiness, excitement, and joy. Negative affect refers to the tendency to experience negative emotions such as sadness, fear, and hostility. People with a high positive affect are more likely to see their work as enjoyable, while employees with a high negative affect often experience their work environment as unpleasant and stressful. Negative affect increases the risk of developing a burnout, while positive affect can actually decrease the risk of developing a burnout.

- Optimism

Optimism is the tendency to believe that good things will happen in the future. Optimism would be negatively associated with burnout, as optimists most likely see their work stresses as temporary. Pessimists, on the other hand, would be more likely to view work stressors as permanent. Pessimistic people therefore have a greater chance of becoming burned out.

- Proactive personality

Proactive people look for opportunities, get into action, show initiative and persevere until change has taken place. A proactive personality can therefore lower the chance of getting burned out. He/she would be more likely to choose an environment that is open to making changes than someone with a reactive personality.

- Resilience

Resilience is the extent to which a person can handle stressors without experiencing psychological or physical strains. Resilient individuals believe they can control things that happen to them. That is why resilient workers see difficult work situations as challenges rather than threats. Resilient employees, therefore, probably have less of a chance of developing a burnout.

- Type A Personality

A type A personality describes the extent to which a person is hostile, aggressive and impatient. People with a type A personality often view the work environment as negative and tend to see small things as unfair. They are more likely to be stimulated and take things personally, to which they are more likely to give a negative response, such as complaining or getting angry. This often provokes a negative reaction from colleagues and can lead to the colleague in question being avoided. This can make someone feel negative about themselves and lead to them becoming even more negative as a result. In addition, people with a type A personality are more likely to choose a stressful job and are more likely to provoke stressors. Research has shown that people with a type A personality are, therefore, generally more prone to developing a burnout.

Risks for a Burnout

Sources:

Alarcon, G., Eschleman, K. J., & Bowling, N. A. (2009). Relationships between personality variables and burnout: A meta-analysis. Work & stress, 23(3), 244-263.

Bateman, T. S., & Crant, J. M. (1993). The proactive component of organizational behavior: A measure and correlates. Journal of organizational behavior, 14(2), 103-118.

Bowling, N. A., Beehr, T. A., & Swader, W. M. (2005). Giving and receiving social support at work: The roles of personality and reciprocity. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 67(3), 476-489.

Costa, P. T., & McCrae, R. R. (1992). Normal personality assessment in clinical practice: The NEO Personality Inventory. Psychological assessment, 4(1), 5.

Kobasa, S. C., Maddi, S. R., & Kahn, S. (1982). Hardiness and health: a prospective study. Journal of personality and social psychology, 42(1), 168.

Lau, B., Hem, E., Berg, A. M., Ekeberg, Ø., & Torgersen, S. (2006). Personality types, coping, and stress in the Norwegian police service. Personality and individual Differences, 41(5), 971-982.

Magnano, P., Paolillo, A., & Barrano, C. (2015). Relationships between personality and burn-out: an empirical study with helping professions’ workers. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Research, 1, 10-19.

Maslach, C., Schaufeli, W. B., & Leiter, M. P. (2001). Job burnout. Annual review of psychology, 52(1), 397-422.

Piedmont, R. L. (1993). A longitudinal analysis of burnout in the health care setting: The role of personal dispositions. Journal of personality assessment, 61(3), 457-473.

Spector, P. E., & O’Connell, B. J. (1994). The contribution of personality traits, negative affectivity, locus of control and Type A to the subsequent reports of job stressors and job strains. Journal of Occupational and Organizational psychology, 67(1), 1-12.

Van Katwyk, P. T., Fox, S., Spector, P. E., & Kelloway, E. K. (2000). Using the Job-Related Affective Well-Being Scale (JAWS) to investigate affective responses to work stressors. Journal of occupational health psychology, 5(2), 219.